Features

Livestock Barns, A Stock Car Track & Country Superstars: A Love Letter To Fan Fair

“You won’t believe it,” raved Ronna Rubin, Warner Nashville’s publicist for Dwight Yoakam, Emmylou Harris and Randy Travis during the glory days of New Traditionalism in the ’80s.

“There is nothing like it.”

“It’s one of those things that must be seen to be believed,” offered Kay West, lead publicist at MCA Nashville. Considering she’d come from Penthouse in New York City, that was a strong assessment. But Fan Fair was truly something that defied words.

Pulling up to a corrugated steel building on the edge of the Tennessee State Fairgrounds to get my credentials, I wasn’t fully prepared. Inhaling a fair amount of packed dirt fair funk, the humidity clung to you like a cloak. Temperatures veered to one side or the other of 90 degrees; but that humidity made it feel like a death sentence sauna.

It literally was a fairground. Livestock barns, sheds to build pens under, scalded blacktop breaking down and tattooed with tar. And down a pretty steep hill, the Nashville Motor Raceway – usually home to stock car racing – housed concerts each label presented to showcase their stars on its blistering asphalt.

Seventeen thousand would descend upon this place, many annual attendees. They came year after year for the stars, the shows, the chance to be up close and personal with everything they loved about country music. Big hair, polyester pants, overalls, halter tops, go-go and cowboy boots. Many of them deploying paper fans with the “Hee Haw” donkey or Minnie Pearl’s shining smile. It was a time, and truly unlike anything I’d ever witnessed.

More jaw-dropping: enter any building, prepare to see row after row of booths. Some were for record companies, products, famous artists like Loretta Lynn and Charley Pride, up-and-coming artists like Travis Tritt with his giant black guitar and people who you’d not only never heard of, you knew didn’t have a chance in the world of making it.

Little Tonya Opry and Little Tonya Indiana with their corkscrew curls and cowgirl outfits straining at the seam were given the same reverence Conway Twitty received. Like Dorothy in Oz, I remember sucking in my breath, whispering, “Toto, we’re not in Kansas – or even Florida – any more!”

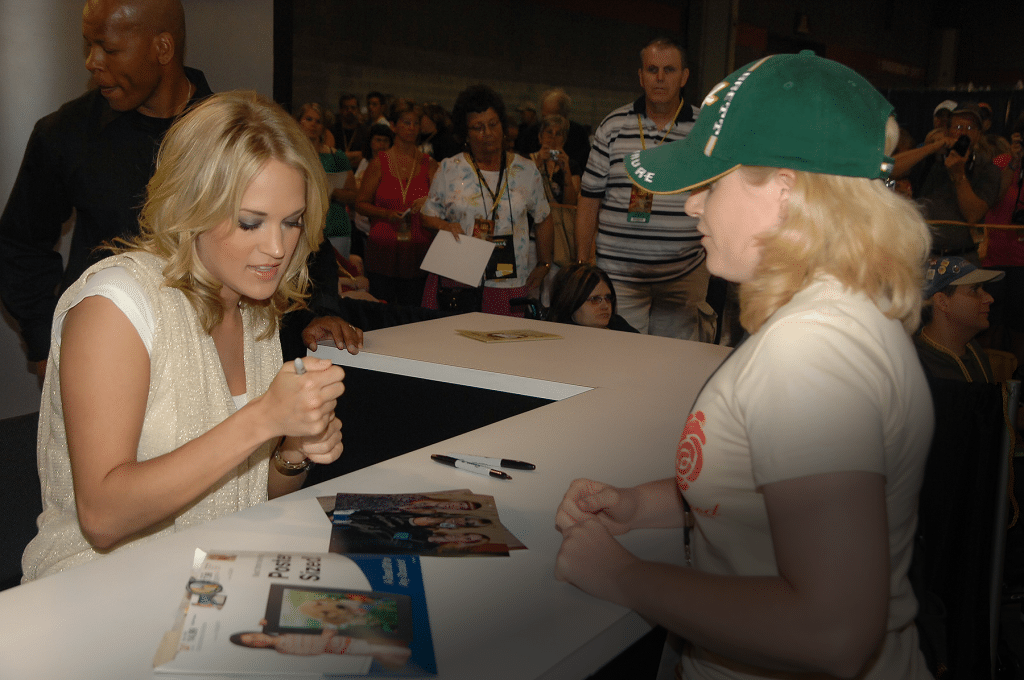

The thing was, Fan Fair was so down home and homespun, it was hard to wrap your head around. Stars would pull up to the same place I’d picked up my credentials, get on UTVs and be whisked to the building they were signing in; whipping by fans, who’d squeal with delight at the star or just a person with a record deal who’d flown by.

“Ron and I had had two hits,” Kix Brooks remembers. “We were working on our third, but the fans would get so worked up, they made you feel like a great big star. It was crazy, but it felt so good, you didn’t care.”

Not that there wasn’t a hierarchy at work. Early in his career, Kenny Chesney made the move from signing in his record company’s booth to getting his very own. Positioned between Alan Jackson, already a young buck superstar, and Billy Ray Cyrus, hitting the peak of his super-powers, it was bleak.

“There I was, trapped between two of the biggest stars in country music, both being swarmed by fans,” Chesney recalls. “And I’m sitting all by myself. A few of the fans felt sorry for me and asked for my autograph. They told me not to worry; I might be as famous as those guys some day.”

Chesney, country’s biggest ticket seller this century, laughs now. But back when Fan Fair, the four day extravaganza was more 4-H than Five Star, there was a real sense of fans engaging in the younger acts’ fate. People bragged about seeing Reba McEntire, Vince Gill or Patty Loveless at their first Fan Fair, watching their stars rise.

Heck, a young Loveless walked through Gill’s line, told him how much she loved his singing, and said, “One day, I want to sing with you.” Gill’s response didn’t belie his “Yeah, right” internal response. Loveless later provided mountain harmony on his first No. 1 “When I Call Your Name” – and teamed for the double Grammy-winning “Go Rest High on That Mountain.”

That hunger to discover something no one else knew, to get more autographs than your friends led to creative signing opportunities. Beyond child stars and Jimmy Dean hawking sausage, Country Song Round Up would require writers to take shifts in their booth; announced over the intercom just like Sawyer Brown or Eddie Rabbitt.

“In Booth 236, for Country Song Round-Up, it’s Holleeeee Gleeeeeeson…”

Stacks of magazines – to give away, priming the pump for subscriptions – would be stacked up. Smile and sign, make people believe you were an authoritative link to their favorites. Only my first year, rocking a Johnny Lee story long after “Lookin’ For Love” was a golden oldie, Marie Osmond was signing in the booth that connected to ours to make the corner.

It was the year she’d released her Madame Alexander dolls, and the fans were wild. A crazy, stampeding horde went slamming forward and sideways; the long card table we were sitting at shoved, bucked and lunged towards the peg board divider behind us.

Holy crap! I was going to die signing copies of country’s oldest fan magazine, a martyr to Marie Osmond’s rapacious fans.

It sounds surreal. It was just another day at Fan Fair.

Surreal was Garth Brooks, at the height of redefining not just what country could be, but pop music, too, walking onto the Fairgrounds unheralded. Standing under one of the metal roofed open sheds, legend has it, he didn’t even take a potty break. Instead he delivered for 23 hours and 10 minutes in 1996; signing and posing for pictures with every single fan who stood in a line that wrapped all the way around the fairgrounds.

Not everything was quite that operatic. Mostly, it was a chance for artists – from The Judds and K.T. Oslin to Randy Travis and Tammy Wynette, Steve Earle to Dolly Parton – to welcome the fans to their home, to show them some hospitality, play a charity softball game for St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital and share their music. Sure, there was a “free lunch,” provided by the Odessa Chuck Wagon Gang, but it was the only way to feed the people in this pocket of land far from downtown, Green Hills or Franklin, Tennessee.

Two or three times a day, a label would host a show. The lesser labels were stuck on that track in the scalding afternoon sun. The night shows would sometimes be plagued with mosquitos the size of hovercraft. And those shows – on the double-wide stage, one live, the other being set-up – were gladiator games of the biggest and the newest, performing to exert dominance or introduce the future of country music.

Blood sport for the artists, it was also the party of the year for the industry as publishers, agents, wanna-bes, DJs and anyone who could find a pass mingled backstage as if they were somebody. The poor acts, hiding on their buses, trying to save their voices and not offend the hoards who’d gather by the door.

Some acts didn’t bother showing up. Too cornpone. Too hay bale. But with the Johnson Sisters – Loudilla, Loretta and Kay – running IFCO (International Fan Club Organization), it wasn’t just the fairgrounds for those fans who journeyed from France, Australia, Canada and Japan.

The Johnsons created a web of people who’d trek from their home to rub elbows at newcomers Jo Dee Messina’s or Terri Clark’s Fan Club Parties pulled together by their mothers or special get-togethers with old guarders John Conlee, Eddy Raven, the Oak Ridge Boys or Kathy Mattea.

Still few things compared to the IFCO-driven Music City News Awards, where the mighty Statler Brothers dominated. Fan-voted, it kicked off the week and – hush-hush – the Statlers’ wins came because a subscription was included in their fan club membership package. It seemed perfect given everything else.

“It was a county fair,” muses Tony Conway, who now manages Alabama and staged the first 11 CMA Fests. It wasn’t even a state fair, and there was a certain amount of controversy when it moved downtown. Having started at Municipal Auditorium, it was certainly a step up when Fan Fair moved out of downtown. But it could only accommodate 17,000, so there was only so big it could ever be. It was perfect for what it was, but country music was becoming so much more.”