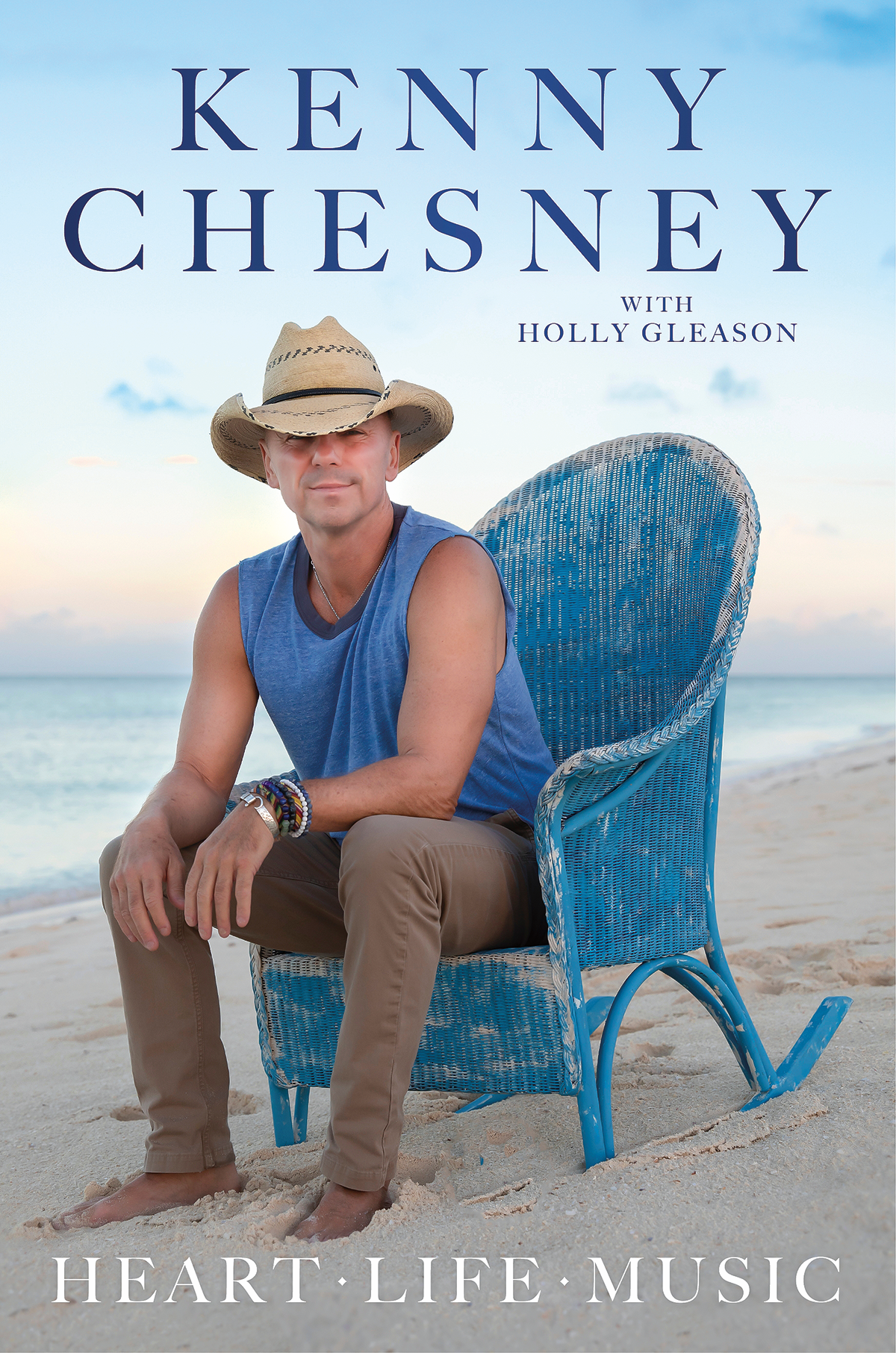

Kenny Chesney’s First ‘True Headlining Show’ (Excerpt From Chesney’s ‘Heart*Life*Music’)

In this trade exclusive excerpt from Kenny Chesney’s “Heart*Life*Music,” the moment arrives when the two-decade stadium-sized headliner truly comes into his own. The book comes out Nov. 4. The book can be pre-ordered now here.

I could sell 2,000, even 3,000 tickets in a lot of places. That’s not a real “headlining tour,” just dates in small halls. We’d done a lot of “compassionate business,” as my friend Shep Gordon, who manages Alice Cooper, likes to say, with the fair buyers. They’d been great to us.

But I needed to sell “hard tickets.” We needed to be smart, be- cause if you go too early and don’t do good business, you handicap your growth…

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, halfway through the tour, we were having a pool party. Everyone loved the sun, water, and unwinding that goes with it. Clint and Louis Messina, who’d promoted those Strait stadium tours, were headed straight for me. These are not beach people. Clint looked like a business guy and Louis looked like a rock and roll promoter who’d not only done tons of dates with the Rolling Stones, but he’d created the legendary Texxas Jam.They were sweating a little, so I hid my smile. “What’s up?” I asked, sitting up on the chaise lounge where I’d been working on my tan.

“We’ve been talking,” Clint said. Ever the manager, Clint was as voracious about being a manager as I was being an artist. “You’re going to headline next summer,” Louis said, directly.

Whippet thin, not overly tall, his nervous energy pulsed through his skin. Louis wasn’t playing.

“Uh . . .” I figured they’d come to tell me about a big tour for 2002. Those things usually book a year, eighteen months in advance.

Headlining?

“I saw your merch numbers jump on that second Strait tour,” Louis continued, matter-of-factly. “They’ve jumped again out here. T-shirts! That’s how we measure passion. That really says something.”

The sun was out, I had a hand up over my eyes and was squinting. I couldn’t read Clint’s face, but it didn’t matter. He wouldn’t suggest this to fail.

Did I believe in myself in that moment enough to say yes?

A lot of indicators were in play. I’d had seventeen hit singles, two years with George Strait and strong dates on my own. Plenty of acts decide they’re big deals, get out there as headliners, and implode.

The sweat was starting to bead up on the guys. I figured, “Trust your people.”

Exhaling, I responded, “If you really think we should do it . . . Okay, let’s do it.”

West Palm Beach was the perfect place to start the tour. Big country market, South Florida’s filled with people who work. It felt like the man I was becoming. Coral Sky Amphitheatre, as it was called, was far enough outside of town, it wasn’t meant to be a big fancy place to go to shows.

A classic pavilion with 8,000 seats under the cover and a half circle of grass that could hold another 12,000, it was a good place to start a tour. Also, to kick off the next phase of a career that almost felt like a new beginning.

We arrived a few days early, to load in and rehearse. I wanted the band to feel confident in owning that stage. It’s easy when you’re playing air guitar to think you know how to do it. It’s another thing when there’s cables and speakers, risers and what have you everywhere.

After a fall of small arenas to get ready, I was leaving nothing to chance. Enough people in Nashville were sure we couldn’t pull it off, I wasn’t going to give them any reason to be right. Plus, we loved being onstage, playing these songs. January in West Palm Beach was warm enough, not humid, with a hint of salt in the air. Every night when we went onstage for rehearsal in our T-shirts and shorts, I’d mentally measure the distance to the back of the lawn. Clayton Mitchell, my guitarist; Wyatt Beard, on keyboards; and Nick Hoffman, with his fiddle, were determined to play with a showmanship that matched their musicianship.

I had a rock-solid foundation to work from. Sean Paddock on drums, Steve Marshall on bass, Tim Hensley on acoustic guitar, and Jim Bob Garrett on steel played country music for all it’s worth. We’d have dinner, jacked up on the spirit of what was about to happen. Everyone talking in catering about ideas they had, something that sounded extra good.

As the day’s heat broke and the sun went down, we’d get onstage to run the entire show. We were learning the momentum, how one song built and broke into the next. There’s a rhythm to a great set list, a way it builds, ebbs, rises again, and pushes you over the top. We were looking for maximum delight.

Finally, January 31 arrived. We did a long sound check in the afternoon, taking our time. That jagged guitar sound from “Live Those Songs Again” floating into the hot South Florida afternoon; it felt so right. Maybe people weren’t doing that, but I knew our fans—like me—would love it.

Out on the lawn, a single woman was dancing. Whether she was an usher, a box office person, or caterer on break, I never knew. But I can see still her hands in the air, hips twisting—figuring that said everything.

Before the show, there was the usual rushing around. Opening acts getting road cases in dressing rooms, gear onstage, asking for meal tickets, receiving their laminates. Security people checking in with the ushers, someone setting up an area for meet and greet. How many shows had I been grateful just to be on the bill?

Wanting to mark the moment, I gathered everyone who’d played a part into this tiny green room for a picture. Louis Messina; Rome and Kate McMahon who routed, settled, and marketed the dates; Joe Galante; Tom Baldricca and his whole radio promotion team, Tony Morreale and Jean Williams; Dale Morris; Clint Higham who’d work with Louis to make it happen; and the band! We were a gang of music, moving into a space no one expected.

There was a full moon hanging beyond the lawn. Palm trees stood in silhouette against it. So did all the people on the lawn who got up to dance, throw their arms around one another, and sing these songs with us.

“Why not be bold?” I thought.

We opened with “Young,” announcing unequivocally this is how our future will sound. We were a month into the single. Though the album wouldn’t be coming until May, “Young” landed like an established hit, people screaming the chorus as if they were declaring their soul to the universe We didn’t sell out, but close to 12,000 people packed the pavilion and filled out the lawn. Toward the end, the general admission folks surged toward the stage. We told security to let them come.

Maybe because it was my audience, that energy was breaking over us in wave after wave. Untamed and loud, it kept rolling. Trying to not get so excited we threw the songs into tempos way too fast to recognize, it was a sustained rush. In a space where music was the ultimate way of letting go, the band, fans, and people working were caught up in the music together.

Coming offstage, I hugged everyone in the wings, then bolted back out onto the stage with a force I don’t think I recognized. We came to play, and man, had we.

The Southern swagger of “Keep Your Hands to Yourself” has its own velocity. Grabbing the mic, throwing my boot onto the monitor, I tore into that opening line and kept going. We had delivered our first true headlining show. And people loved it. Loved it so much I could see them pointing, cheering, laugh- ing. We had the Georgia Satellites, followed by John Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane,” a perfect benediction for all of us kids nobody saw coming.

So caught up in the moment, I didn’t realize one small thing: When I leaned into that first line with my foot on the monitor, I literally busted my inseam. The entire space where the seams come together had torn open, and all of West Palm Beach got a look at what I was packing.

The night was so inspiring, I didn’t care. I laughed. Truly, opening night, I had left it all onstage. After the pictures were taken, the last handshake and hug was given, and the memory of all those cheers died off, I went back to the state room on my bus to take it all in. Rather than obsess about the seam of my jeans tearing, all I thought about were the surges of energy that kept slamming into us—the way people screamed and sang along, the bliss on their faces.

They were so passionate. Everything I’d believed about “Young,” this shift I had wanted, manifested right there. I’d seen it. This sound, the tropical rhythms that were coming, but especially the rock energy changed the way people absorbed country music. Making something passive into an active force of life.

Overwhelmed, I took in the stillness. I wrote a contract with my soul that night. Sitting alone in the back of my bus, idling in the parking lot, I made a commitment. No matter what it took, demanded, or required, I was going to give everything to this. I was going to push the limits but never lose sight of who the people living inside these songs were. For me, giving them anthems they could put their lives inside, feel seen and understood, was a big piece of it. But even more, when they came to—literally—live those songs together, I wanted to absolutely deliver them with complete immediacy.

I wasn’t going to give a lot. No, it was more. I wasn’t going to save anything for myself. Whatever it took, however I had to deliver it, I would give it all. That was my mission. I knew what music meant to me. I wanted this music to mean that to them.

Daily Pulse

Subscribe

Daily Pulse

Subscribe