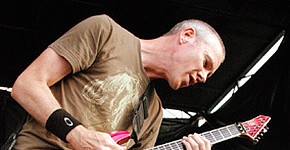

Helmet’s Page Hamilton Talks ‘Betty’

Pollstar talked to Hamilton in late January, ahead of the U.S. Betty tour that launches Wednesday with a gig in New York’s Bowery Ballroom. The anniversary festivities began last fall with a Betty tour through Europe.

Hamilton formed the alternative metal band in New York City in 1989. The group went on to influence acts ranging from System Of A Down to Korn. Betty was the follow-up to Helmet’s sophomore album and major label debut, 1992’s Meantime. Hamilton discussed the pressure the band faced after the success of Meantime, which was certified gold and is still Helmet’s top-selling album to date.

The experiemental Betty earned plenty of praise from critics and debuted at No. 45 on the Nielsen SoundScan chart, marking the band’s highest charting album. The track “Milquetoast” was the album’s biggest hit, thanks in part to its inclusion on “The Crow” soundtrack. Additional singles include “Biscuits for Smut” and “Wilma’s Rainbow.” All of the songs on the 1994 LP were written or co-written by Hamilton except for a cover of the 1931 jazz standard “Beautiful Love.” If you’d read up on Hamilton’s background it makes sense – he holds degrees in classical and jazz performance and continues to perform jazz on the side.

After multiple lineup changes and a hiatus that spanned 1998-2004, Hamilton is the sole original member of the act. Along with the vocalist/guitarist, the current lineup features Dan Beeman on guitar, Dave Case on bass, and Kyle Stevenson on drums.

Looking back on Betty, how do you view the album and its impact on music?

I don’t really think about things in terms of its impact on music but I can certainly talk about the recording and the process and the different pressure that came with having some moderate success with the band after just being an indie band that started at CBGBs. The Meantime record came out and … people who were into heavy metal kind of got excited about it and our audience expanded tenfold. The people who had no opinion about what we were doing when we made Strap It On and Meantime suddenly had opinions about what we should do with Betty.

And because I like to shoot myself in the foot we sort of went against the grain and did the cover, which was used in Australia University as an example of subversive art. I just thought it was funny and a cool cover. It’s interesting that 20 years later the Betty tour has been more of a big deal than the Meantime tour was two years ago. We did 40 shows in Europe and we have this U.S. [tour] coming up that keeps getting extended. It’s been fun. The recording [had] sort of ups and downs. I was kind of in a personal place of turmoil and …. I think because of the success of the band and attention, it kind of wrecked the relationship that I was in. And there was a lot of turmoil in the band as well, because we were, like I said, just used to playing the Pyramid Club and CBGBs and the Middle East in Boston and small clubs around the country. But at the end of the day you just have to sit down and write what you feel confident and comfortable doing. And we were always united when it came to the music. The three of us – John Stanier and Henry Bogdan and myself.

It seems like it would be kind of difficult to put all that pressure aside and just write but obviously it worked out for you guys.

Yeah, I’m happy with the process. Sometimes you need to shake things up a little bit. Strap It On and Meantime were self-produced albums and then after we had success – or success on an indie level, having sold close to a million records with Meantime – to all of a sudden have people take notice, as I said, that didn’t care before. And everybody’s like, “Who’s going to produce the record?” And I was confused – I said, “I thought I did a really good job (laughs),” you know. But they want you to be like mega-band, like 6 million records like Nirvana or whatever and Helmet was never as accessible as Nirvana and it wasn’t meant to be as accessible as Nirvana. I love Nirvana but we were two completely different kinds of bands. Because they had had that success coming off of SubPop and we were on Amphetamine Reptile everybody’s like, “Oh, this is the next Nirvana.” And I’m like, “Have you listened to us? (laughs) We scare people.”

I had friends come to my bartending job in the East Village after they saw us at CBGB’s and because I’m a relatively mild mannered, short-haired, clean-cut guy, my friends came up to me and they’re like, “What the fuck, dude? Like, you’re so scary on stage! And I’m like, “Really? I’m just kind of expressing myself.” They’re like, “We didn’t recognize you.” And I’m like, “It’s coming from a deeper place. That’s why I play music. It’s a form of expression that’s beyond the English language.” I still feel that way about it and I still love doing it.

It’s been interesting doing these Betty shows because there are songs on the album that were never performed live, even back when the album came out. So I had to rethink sounds, set flow and stuff like that and it was a real challenge at first. … It’s been really fun and it will certainly, probably influence the writing that’s going into the next album.

When you first released Betty did you realize that you had created something that would be celebrated two decades later?

You know, I feel that way about everything. I was always very confident in my band’s ability to do something unique and powerful. We were of one mind when it came to the music even though we didn’t always personally necessarily get along. … It was an odd collection of personalities. John and Henry were with me from day one and they’re just both phenomenal musicians, meaning they have technical facility on their instruments but they play from that place that I like to play from, that kind of takes you out of [a] self-conscious place. And that’s what music is. It always has been for me. I always felt that we were doing something good. And it’s not for everyone, as I’m sure you’ve probably read bad reviews as well. Each album it seemed like there would be a handful of people that loved the last album that didn’t love the next album. … I think that’s a positive sign – if you ruffled people’s feathers a little bit and don’t repeat yourself, then you’re kind of doing something right moving forward. I’m happy that it’s held up. I’ve gotten a lot of nice emails from fellow musicians and stuff. I did a thing on the Linkin Park record and Mike Shinoda was very gracious and said, “Man, Betty’s rad. So cool you’re doing this.” It’s good to hear that kind of stuff from people because at the time … I know there were some good reviews but there were also people who didn’t like it.

I think the key is to just be honest and always make it about the music and not make it about, you know, cool clothes and makeup and whatever. That’s fun stuff – I played with David Bowie and I loved looking at his different periods but the bottom line was he always wrote great songs and still writes good songs and it’s always about the music. So I figure, people, critics whatever don’t give Elvis Costello, David Bowie and whoever else a free pass, they’re not going to give me a free pass (laughs). … As a musician you realize you have no control over that so be honest with yourself and write what you feel. If you work and practice every day and continue to read and expand the base of material you have to draw from, then you’ll probably do something good. And I think people who try to cater to a marketplace end up starting to stink. That’s pretty common in rock, in my opinion. I’m a huge jazz nut so I still go back to Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane and Charlie Parker and those guys and they always put out good stuff, everything from day one to the day they died. And that’s because they’re musicians first. And that’s important. That’s my lecture for young songwriters. (laughs)

Like you said, if you’re just trying to write for the critics, it’s not necessarily going to work out for you.

I’ve talked to so many young bands, because I produce bands … somebody gets in their ear … on one level that happened to us. I said we went with a co-producer for [Betty] because they want to take you to the quote/unquote next level. Well the co-producer kept telling me … “I’ve never worked with anybody who’s so together.” And I’m like, “Well, yeah, because I work and I know what I want to do.” But I’ve worked with a lot of young bands … and I’ve advised them to ignore the industry people, meaning record label, management whatever. Make the music that you believe in. Write, be honest with yourself. … If you stop being true to what you do, you’re not going to please everybody – ever. Like he 14-year-old kid who came up to me and said, “I don’t like the Betty cover. (laughs) I thought the Meantime cover was so much cooler.” And I’m like, “Oh really? I think they’re both pretty cool. You just have to expand your mind.” And he’s like, “And what’s with that jazz thing on there?” I’m like, “Oh, isn’t that cool?” He’s like, “No, I don’t like it.” I’m like, “OK (laughs) Well, you’re 14 now so maybe when you’re 24 …” Or he’ll be 34 now. Maybe he likes it now.

Do you have any favorite tracks to play live?

I love playing those songs that were never performed [live]. I was nervous as hell the first time I had to do “Sam Hell” because it’s me by myself, pretty much, and then I made Danny and Dave come in on bass and guitar for a little bit of support. On the album it was just me, I did the banjo and acoustic guitar and then my voice. And “Biscuits for Smut” was another one that we had dropped from the set because it requires a very odd tuning. And we didn’t take the extra guitar. But I kinda figured out a way to do it with the guitar I’m using. I just had to retune one string. Those have been fun because they feel brand new, they feel really fresh. I find when you play things that you haven’t played next to things you have played, it breathes new life into the ones that you’ve maybe over-played 3,000 times or whatever. I think I’m in the 3,000 show zone at this point.

I was wondering if it was bittersweet at all to celebrate Betty without having Henry and John there? Or if the lineup change happened so far in the past that it doesn’t really matter at all or you don’t think about it.

I don’t think about it. But. What I learned five or six years after the band broke up was that I had guilt that I handled things the wrong way, could have done things differently. It’s nothing new to rock music, to bands. It’s been going on from the dawn of man that bands break up and rifts develop between band members. And I realized that it was completely out of my control. It wouldn’t matter if I sat down with them and said, “What’s the deal? Why are you upset with me?” Those things are beyond my control. I reached out early on and then a friend of mine, Andrew Bonazelli, who writes at Decibel, wanted to do a thing on the Meantime album as a classic influential album and both guys passed. So obviously whatever problem they have with me, they have and it’s beyond my control. I wish them nothing but the best. I think they’re both phenomenal musicians. And we never had great communication … It’s my responsibility as well as their responsibility. So as three men we can either sort of choose to communicate or not and they’ve chosen not to.

So at a certain point I have to move on with my life. And when [producer / Interscope Records co-founder] Jimmy Iovine called me one year when I moved to Los Angeles. He said, “You need to make a Helmet record.” I said, “Well, Helmet broke up.” He said, “You are Helmet. Make a Helmet record.” As the guy that formed the band from the ground up with an ad in the Village Voice, obviously I’m very attached to the music and I missed playing it. So I said, “Absolutely.” And the musicians who were playing with me at the time – John Tempesta, who’s in The Cult now, and a couple of guys from different bands — they were reluctant at first because they held Helmet at high esteem and that was the band. But as the singer and writer and arranger and producer of the band, I guess I’m the one most qualified to form under my own band’s name. I never ruled anything out but at the same time I don’t feel apologetic. As I’ve had years and years to think about it, I did nothing criminal in the relationship with the guys. Sometimes resentment builds in bands. I’ve had fights with pretty much every band member I’ve ever had, and that includes even playing in David Bowie’s band, there was tension with people and I was just a hired gun. You’re going to step on people’s toes if you’re an opinionated person (laughs), which I am. I always tell everyone, “Nothing is ever personal. It’s always about making the music the best it could be.” And I feel like I’ve earned that right because I still practice guitar every single day. I have no life (laughs).

In your press and on Wikipedia, Helmet is described as a “thinking person’s heavy metal band.” What’s your stance on that label?

I think it’s funny. I blame John Stanier for that one. We did an interview like a thousand years ago and John is extremely talented as a drummer, he’s maybe less eloquent as a speaker. And some guy had said something about us being “thinking man’s metal so John quoted that in an interview. It was like a caption, like a soundbite thing and I don’t think I’m too good for soundbites. … So John said that, he repeated something that somebody had said to us or called us and it’s stuck for all these years. It’s funny.

We were playing with Guns N’ Roses and Sebastian Bach was on the bill as well and we shared a wall in some hockey arena in Canada. I walked in the dressing room and the guys were laughing and Sebastian was like, “Fucking Page dude’s cool; he’s a rocker like us!” And it was that “thinking man’s metal thing.” Gene Simmons walked in one day and said, “Where is everybody? Is somebody in the bathroom getting a blowjob?” And he looks at me and he goes, “Oh, I forgot, you read books.” So I was unaware that I had this reputation that I was some kind of egghead, intellectual guy because I drink too much and make an ass of myself like everybody else and have fun and I play in a rock band, you know. I didn’t get in a rock band to grow up. But yeah, I read books and I use my brain 10 percent of the time, which is maybe 9 percent more than most dudes in rock bands (laughs), so I guess if you want to call it thinking man’s metal, let’s go with that.

Well, I guess there are worse things you could be called.

There were some great ones … I don’t really care that much about clothing and [my ex-wife] would shop for me, she’d go to the Gap and buy me a like a striped T-shirt. And I’d be like, “Fine, this looks good.” So somebody was like, “They’re Gap-core.” And Stanier would wear those button-down shirts with his hair pomade and stuff. I think it’s funny. People will despise you for whatever reason they chose to. I’ve always maintained, “Shut the fuck up, drop the needle, listen to the music.” [Helmet is] not for everyone but it’s well written, constructed and it’s unique and as we’re finding out, it’s standing the test of time. And that’s all you can hope for. And I’ve had so many musicians tell me that we’ve influenced them and that’s always a nice boost to hear from fellow musicians, people from Steve Jordan to Gene Simmons and the System Of A Down guys, people that have said that our band was important to them. And sure, it makes you feel good about what you’re doing, that you’ve done something right, at least. And there are going to be other people that absolutely can’t stand you because you wear Gap T-shirts. That’s their prerogative.

Have you announced a release date for the new album? I had read that it was due out sometime this spring?

No, we’re going to record in the spring. I had a hell of a year. We were in Europe and my father was diagnosed with cancer between the U.S. and the European tour and he passed away while I was crossing the Baltic sea. Now I’m going through stuff with my mother. So everything has changed. I’m writing and we’re going to record in between the East Coast/Midwest leg that we’re about to start and the West Coast dates, which haven’t been announced yet. We’re going to go in for two weeks and record the new album. So it will be [released] at the end of the year, probably. Whenever the people that advise us with our business stuff advise us to do, I’m game. I don’t care when it comes out, just so it comes out this year.

Well, I’m sorry to hear about your father.

Thanks very much. I appreciate it. He was a great dude. A really great guy. And yeah. It’s obviously threw a huge wrench in things this year. And my parents were together for 57 years so my mom is having a hard time too. I actually just booked a flight yesterday because I talked to her a couple days ago and the sound in her voice was not my mom. And so I just booked a flight, I’m flying up there tomorrow and I’m putting this whole weekend on hold.

Well, I’m sure she’ll appreciate that.

Yeah, I called her today and she was very excited.

So one last question, if you could look back on 20 years ago, what advice would you give yourself?

Well, not to hurt the feelings of the co-producer, I would have continued business as usual and done the album ourselves as we did Meantime [which the band produced with Steve ALbini and Andy Wallace] and with Wharton Tiers, who did Strap It On. Because we had a great work flow and it would have taken a lot of strain off of me. All of the other cooks trying to get into the kitchen made it harder on me personally and probably contributed to my relationship breakup and other things. It’s kind of boring but I would just stick to my guns even more than I did and just say, “Nope. We’re not bringing anyone else in.”

And I think looking back I would try to communicate with my bandmates more, rather than just assuming they understood everything. … I think it’s inevitable that the band was going to break up. They left – I didn’t fire them. And after 10 years I think it’s not uncommon for people to get on each other’s nerves.

So does that mean we can expect you’re going to produce your next album?

Yes. Absolutely. Definitely. We work with Toshi Kasai. The albums I produce that are in the U.S., he engineers and has for years for me. I met him through the Totimoshi band, that I produce, who were huge Melvins fans. And he’s been working with the Melvins for years. And they have a studio now in the Valley, together with Toshi. And the Melvins are old friends of ours. … I love working with [Toshi]. I feel confident if I’m doing vocals by myself with an engineer I can bounce ideas off of the engineer – and at this point, if I don’t know what I’m doing, I should probably just do something else (laughs). So yeah, I feel good about it. I’m very excited.

Upcoming dates for Helmet:

Feb. 18 – New York, N.Y., The Bowery Ballroom

Feb. 19 – Boston, Mass., Brighton Music Hall

Feb. 20 – Philadelphia, Pa., World Cafe Live

Feb. 21 – New York, N.Y., The Bowery Ballroom

Feb. 22 – Brooklyn, N.Y., Saint Vitus

Feb. 24 – Lancaster, Pa., Chameleon

Feb. 25 – Washington, D.C., Black Cat

Feb. 26 – Durham, N.C., Motorco Music Hall

Feb. 27 – Charlotte, N.C., Visulite Theatre

Feb. 28 – Atlanta, Ga., Hell At The Masquerade

March 1 – Mobile, Ala., Soul Kitchen

March 3 – New Orleans, La., One Eyed Jacks

March 4 – Houston, Texas, Fitzgerald’s

March 5 – Dallas, Texas, Gas Monkey Bar & Grill

March 6 – Shreveport, La., The Warehouse

March 7 – Fayetteville, Ark., JR’s Lightbulb Club

March 8 – Kansas City, Mo., The Record Bar

March 9 – Omaha, Neb., The Waiting Room

March 11 – Minneapolis, Minn., Mill City Nights

March 12 – Madison, Wis., High Noon Saloon

March 13 – Chicago, Ill., Double Door

March 14 – Cleveland, Ohio, Beachland Ballroom

March 15 – Indianapolis, Ind., The Vogue

March 17 – Ferndale, Mich., The Magic Bag

March 18 – Toronto, Ontario, Lee’s Palace

March 19 – Pittsburgh, Pa., The Altar Bar

March 20 – Newport, Ky., Thompson House

March 21 – Louisville, Ky., The New Vintage

For more information please visit HelmetMusic.com and visit the band’s Twitter and Facebook pages.

Daily Pulse

Subscribe

Daily Pulse

Subscribe