Features

Martin Scorsese’s ‘Rolling Thunder Revue’ Film Captures Incandescent Performances At Heart Of Bob Dylan’s Epic 1975-76 Tour

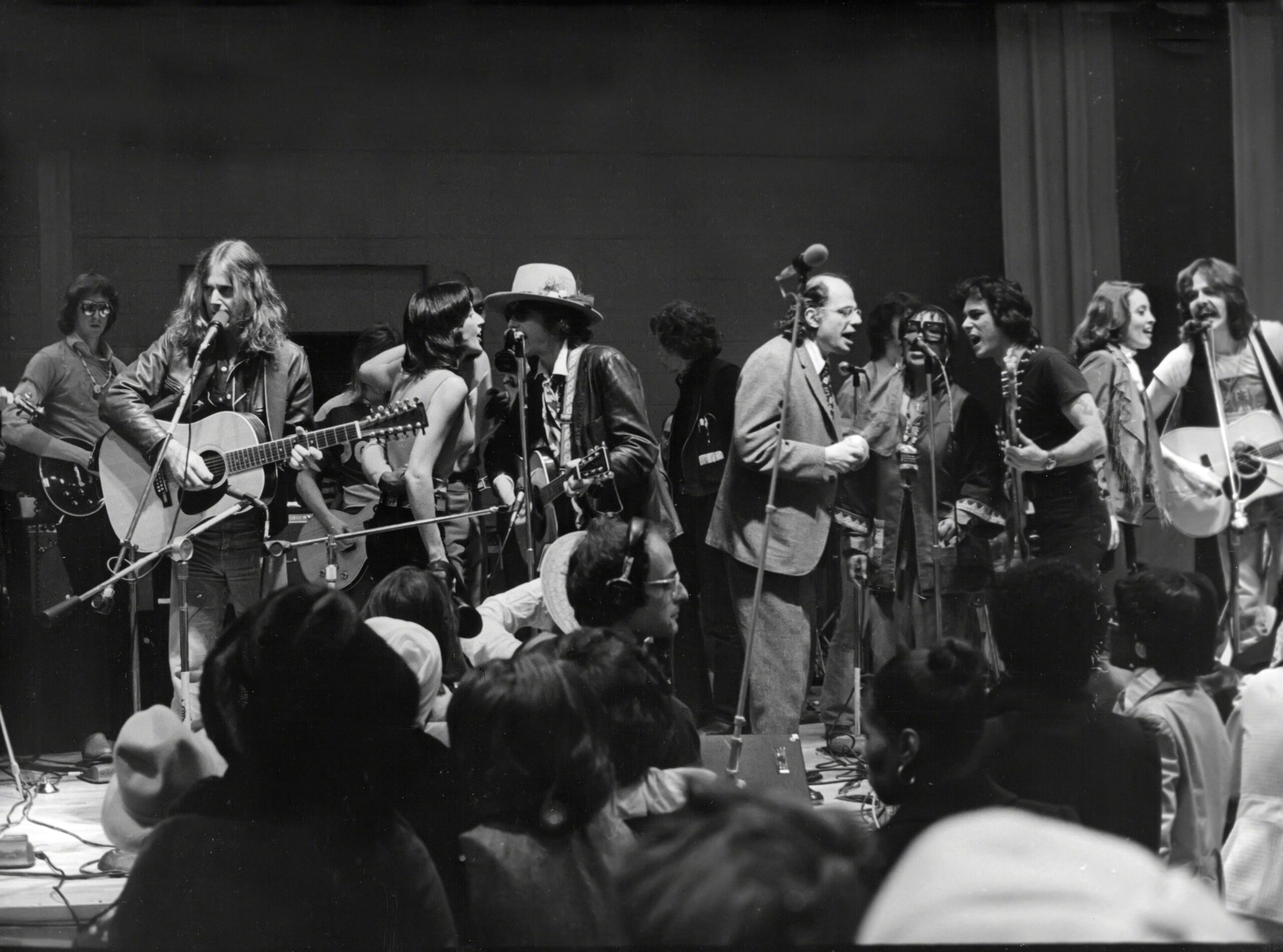

PL Gould/IMAGES / Getty Images – The Story of the Hurricane

Rolling Thunder Revue performers including Roger McGuinn, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Roberta Flack and others perform a benefit concert for Rubin “Hurricane” Carter at the Clinton Correctional Facility for Women on Dec. 7, 1975, in New Jersey. Carter, who was temporarily housed in the facility, was in attendance.

In a scene from “Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese,” currently airing on Netflix, tour manager Jim Gianopolous describes producer Louie Kemp as “a fishmonger who is out of his element, and not very well liked on the tour.”

The “tour manager” is actually the chairman and CEO of Paramount Pictures and was not involved with Dylan’s famed Rolling Thunder Revue, a ragtag tour of small venues in largely secondary and even tertiary markets in 1975-76. Kemp, however, is very real – and did produce the tour that brought Dylan together with Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Roger McGuinn and many others in a historic musical caravan.

To say Scorsese took artistic license (something Dylan helped invent) in making the film would be an understatement. The concert footage was intended for the shambolic film “Renaldo and Clara” and a narrative stitched together some 40 years later uses composite and fictional characters, including scripted “interviews,” and a whole lot of inside jokes and Easter eggs.

But the concert performances are the real deal and highlight of the film. And Rolling Thunder Revue stands as one of the most critically acclaimed, if oddball, outings of its or any time.

Blank Archives / Hulton Archive / Getty Images – Freewheelin’

A typical handbill for Rolling Thunder Revue had space for the last-minute details including venue, date and ticket price to be filled in by hand and distributed 2-3 days before the show.

The contemporary interviews with Dylan are fascinating and the performances are energetic, joyous renditions from the Dylan canon – from early standards like “Mr. Tambourine Man” to the then-new “Hurricane” – in an atmosphere of exuberance not typically associated with the Bard of Rock.

Kemp did run his family’s successful fish business at the time. He and Dylan met as boys attending the Herzl summer camp outside St. Paul, Minn., and have remained friends since – Dylan even invited Kemp to join him and The Band on Tour ‘74, a large-venue outing produced by Bill Graham.

Kemp studied the master and, when asked by Dylan to produce the next tour, Kemp asked Barry Imhoff, Graham’s former partner, to help him organize and book dates. Most importantly, perhaps, was to lend an air of credibility to the secretive tour with its fishmonger producer and fluid lineup.

“What I learned through all my business dealings … was the key to being successful is to surround yourself with good people,” Kemp says of his unlikely entry into the concert business. “Barry knew everyone so it was easy to put all the bricks in place.”

Apropos of the spontaneity at the core of Rolling Thunder, artists invited as guests joined the caravan as it rolled along. Poet Allen Ginsberg came along for the ride as something of a shaman. Mick Ronson joined the band, as did a young T Bone Burnett.

Dylan, coming off the wildly successful Blood On The Tracks and Tour ‘74, was in New York City recording and “he’d been thinking about this type of tour for a while – a kind of musical, mystical, magical, mystery tour with a carnival atmosphere,” Kemp says. “He approached a few people, who all tried to talk him out of it. ‘No, no, you’re too big for that. You should do something like you did in ’74, a big money tour, a big extravaganza in arenas.’” Dylan wasn’t interested.

“I want to do one for the people, something fun; small venues, places where people wouldn’t ordinarily be able to see me and get good tickets,” he told Kemp. “I want it to be fun for the crowds, and fun for the people on the tour.” They brainstormed what they could do.

“We were the pranksters then. I guess Bob and Marty [Scorsese] are the pranksters now, more than 40 years later,” Kemp says. “Barry [Imhoff] made the calls. If I were to call [venues] and say ‘I’m Louie Kemp, the fish dealer from Duluth, Minnesota,’ they’d think, ‘Who is this crazy dude?’ I remember we had an advance guy who used to do the roller derby. The whole thing had such a carny atmosphere.”

The tour launched Oct. 29, 1975 at the 1,500-capacity Memorial Hall in Plymouth, Mass., with tickets priced at $7.50. Promotion was by word of mouth, and handbills for Rolling Thunder Revue with photos of Dylan, Baez, Elliott and McGuinn were distributed two days out.

The concept and promotion may have seemed chaotic, but the performances are sublime with Dylan downright electric, Baez – sometimes adopting the white grease paint “mask” and playfully donning Dylan drag including flower-festooned bowler hat – dancing around the stage in between powerful duets that showed off her famously pure soprano vocals, among the reasons Baez is an American treasure.

The “Rolling Thunder” movie opens with a solo performance of “Mr. Tambourine Man” juxtaposed with a Richard Nixon speech and an interview explaining the tour. “It’s about nothing. It happened more than 40 years ago … so long ago, I wasn’t even born!” present-day Dylan exclaims.

Performances include: an up-tempo rendition of “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” a spine-tingling “The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll” and “I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine,” from the Dec. 4, 1975, Montreal Forum concert; “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” “Romance In Durango” and an especially fierce rendition of “Hurricane,” all from the Nov. 21, 1975, show at Boston Music Hall; additional rehearsal footage, impromptu apartment sing alongs, a concert at a New Jersey women’s prison and the Dec. 8, 1975, first leg finale at Madison Square Garden, the “Night of the Hurricane” benefit for Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the boxer wrongly convicted of murder whose case Dylan championed.

–

A spread of ticket stubs and other memorabilia from Rolling Thunder Revue.

The troupe started with 50-60 people, including artists, stage and film crews, but grew to nearly 100 with assorted friends and hangers-on, Kemp says. Guests who were invited onstage included Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith, Arlo Guthrie, Ringo Starr, Van Morrison and Gordon Lightfoot, but only Joni Mitchell truly joined the circus.

A key scene of the film has Mitchell, during a party at Lightfoot’s apartment, trying out “Coyote,” which became a huge hit from her 1976 album Hejira. It’s in almost perfect form already.

Mitchell was traveling with her then-manager, Elliot Roberts (who recently passed), who asked Kemp about the possibility of joining the Rolling Thunder Revue.

“I said, ‘Sure, we’d love to have her. It would be our pleasure.’ And he said, ‘But there’s one thing: I have to go and be with Neil (Young, Roberts’ longtime client) shortly and I can’t stay.’ He’d go out with her on her tours just like he did with Neil. He said, ‘Will you look after her?’ and I said, ‘Certainly.’ So I did. She stayed for the whole tour and it was great,” Kemp says.

“There was a special energy that flowed through the tour that was unlike anything I had ever experienced,” Kemp writes in his book “Dylan and Me,” scheduled for publication in August. “Audiences felt it too; they knew they were seeing something very special over the course of those four- to five hour-sets.”

No need to do a double-take. A typical Rolling Thunder Revue show ran roughly four hours. If a guest decided to play, it could run to five hours, Kemp says.

But not everyone came to play. Leonard Cohen attended a show in Montreal but declined the invitation to take the stage. Dylan dedicated a raucous performance of “Isis” to him.

The first leg of the Rolling Thunder Revue tour ends with the “Hurricane” benefit in New York. Another would take place in January 1976 at the Houston Astrodome, and the second leg would be booked from April through May.

When it was all over, Kemp quotes Ginsberg summing up the proceedings in his book. “Having gone through his changes in the sixties and seventies, just like everybody else, Bob got his powers together for this show. He had all the different kinds of art he has practiced – protest, improvisation, surrealism, invention, electric rock and roll, solitary acoustic guitar strumming, duet work with Joan and other people – all these different practices ripened and were useable in one single show.”