Patience Is A Virtue: Tame Impala’s Psychedelic Journey From Perth To Arenas

Brian Lima – The Slow Rush To Arena Headliner

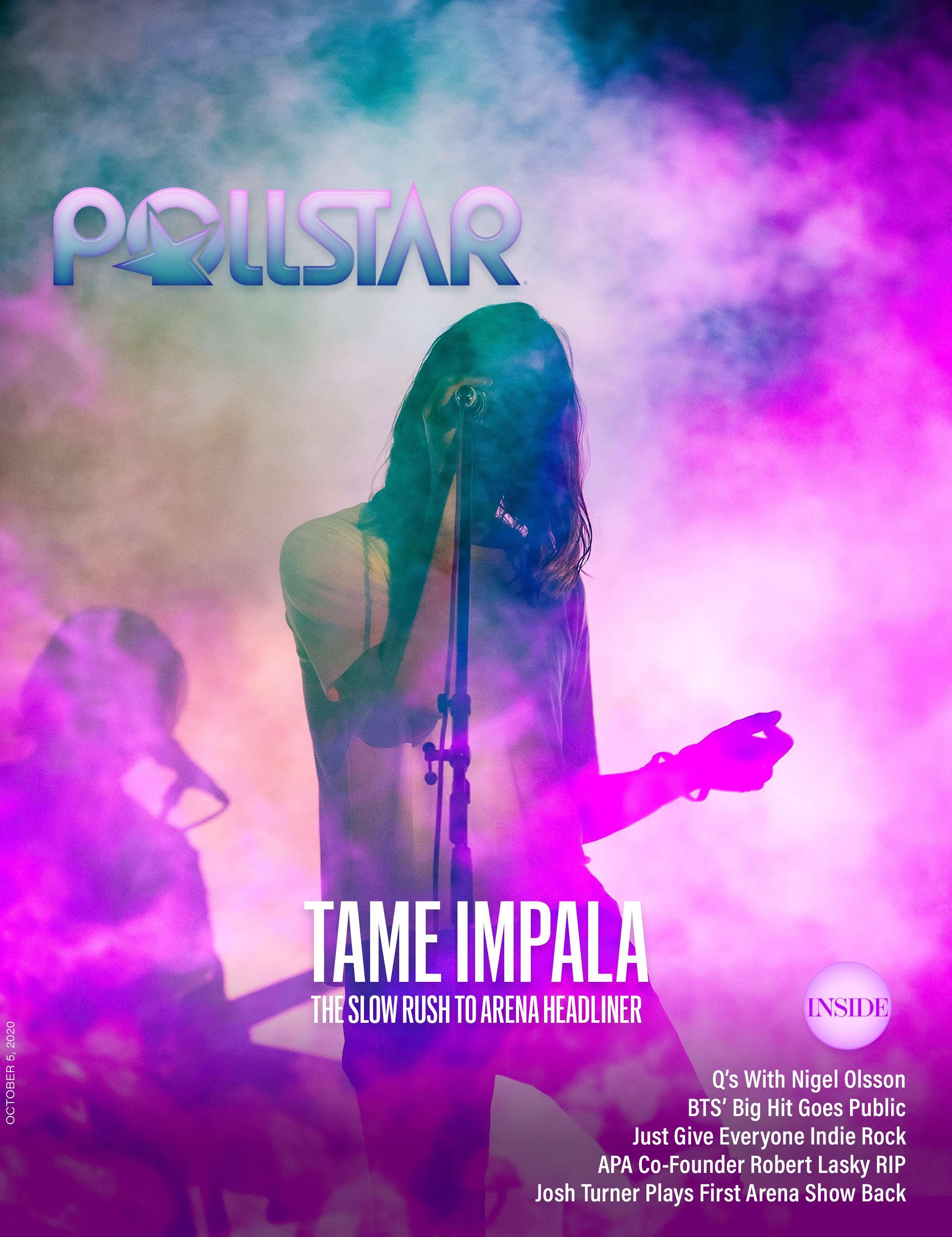

Kevin Parker performs during Tame Impala’s headlining set at Coachella in Indio, Calif., on April 13, 2019.

March 11 should’ve been a celebration for Kevin Parker.

The Australian rocker, better known as the long-haired mastermind behind Tame Impala, was set for a second sold-out night at the Forum in Inglewood, Calif., itself the third night of his first arena tour, which had kicked off with a sold-out gig at San Diego’s Pechanga Arena on March 9. A month earlier, Tame Impala’s fourth album, The Slow Rush, had received widespread praise, debuting at No. 3 on Billboard’s albums chart.

The paid audience that night at the Forum was 12,993. But the figure’s misleading for the same reason that a pall lingered over the arena. Venues were closing across America. Tours were postponing. Within days, Californians would be sheltering in place. Coronavirus had arrived. Some ticketholders hadn’t.

“It was a weird mood,” Parker tells Pollstar from his native Perth, where he relocated early in the crisis. “No one knew what the hell was going on.”

“I remember sitting backstage at the Forum watching the news with the promoters going, ‘Fuck!’” says Tame Impala’s agent Kevin French of CAA.

The mood was downcast. Tame Impala’s manager, Spinning Top Music’s Jodie Regan, recalls French informing her that the band’s next gig at San Francisco’s Chase Center was a no-go, and that the tour seemed in jeopardy.

“We were almost expecting that we might not be able to play that second Forum,” Regan says. “Everyone was scared.”

“I don’t think any of us inside the Forum for the Tame Impala shows fully understood what was about to happen to our world, and to the live concert and event industry,” Geni Lincoln, Forum general manager and senior vice president of live events, tells Pollstar by email. “Looking back, I’m grateful that we could escape with Kevin and his crew even for just a few hours.”

All told, Tame Impala moved 25,986 tickets for the Forum gigs for a total gross of $1.82 million, easily surpassing the band’s previous high marks. But it was a Pyrrhic accomplishment: Tame Impala hasn’t played a show since.

Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty – Final Forum

Tame Impala performs at the Forum in Inglewood, Calif., on March 10, 2020. The band’s Forum gigs were their last before coronavirus forced a tour postponement.

Tame Impala’s rise from psych-rock club staple to arena-headlining zeitgeist began in Perth, Australia’s fourth-biggest city and one without an American analogue. Located in the state of Western Australia, Perth’s population of roughly 2 million is about as far from the continent’s more populous East Coast – home to Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and several other cities – as Las Vegas is from Washington, D.C. To Perth’s immediate east is the Western Australia region of Goldfields-Esperance, a swath of land larger than Texas with a population half the size of Waco.

“I don’t think anyone really understands how isolated it is,” Regan says. “We don’t have any music industry here. There was never any chance that there would be a music industry person that would walk up to your gig.”

The low-stakes atmosphere fostered creativity, which Regan experienced firsthand when the pub where she was a manager, The Norfolk Hotel, opened 180-capacity venue The Norfolk Basement downstairs in the early ‘00s. There, Regan became close with a hot local band, The Kill Devil Hills, and before long began managing them.

Tame Impala emerged from Perth’s interconnected rock scene. In short, Regan caught another band – Electric Blue Acid Dogs, soon rechristened Mink Mussel Creek – at Mojos Bar in neighboring Fremantle and came to manage them. When an unexpected vacancy arose, the band filled it with their friend Parker; to avoid scheduling conflicts, Regan started booking Parker’s other group, The Dee Dee Dums.

“I was stoned and afraid of the outside world,” Parker says. “Jodie was this person that we all looked up to because she was cool as shit. And she was this buffer between us and the outside world – someone that told ‘em all to get fucked, if we needed them to.”

By the late ‘00s, Mink Mussel Creek had splintered, with some members forming Pond – an enduring psych-rock act Parker has an extensive creative relationship with – and Parker reconceiving The Dee Dee Dums as Tame Impala. The roots are important: While Parker records Tame Impala’s studio work alone, his five-piece touring unit has remained remarkably stable and is filled with peers from his Aussie days. Regan, meanwhile, still manages Pond and several other affiliated projects alongside Tame Impala at Spinning Top.

“It was everything, it was all I knew,” Parker says when reflecting on his start in Perth. “We came from a scene where people played down the theatrical side of it and just cared about the music. I wouldn’t be one-tenth of the musician I am today if it wasn’t for those years and years of just playing all the time.”

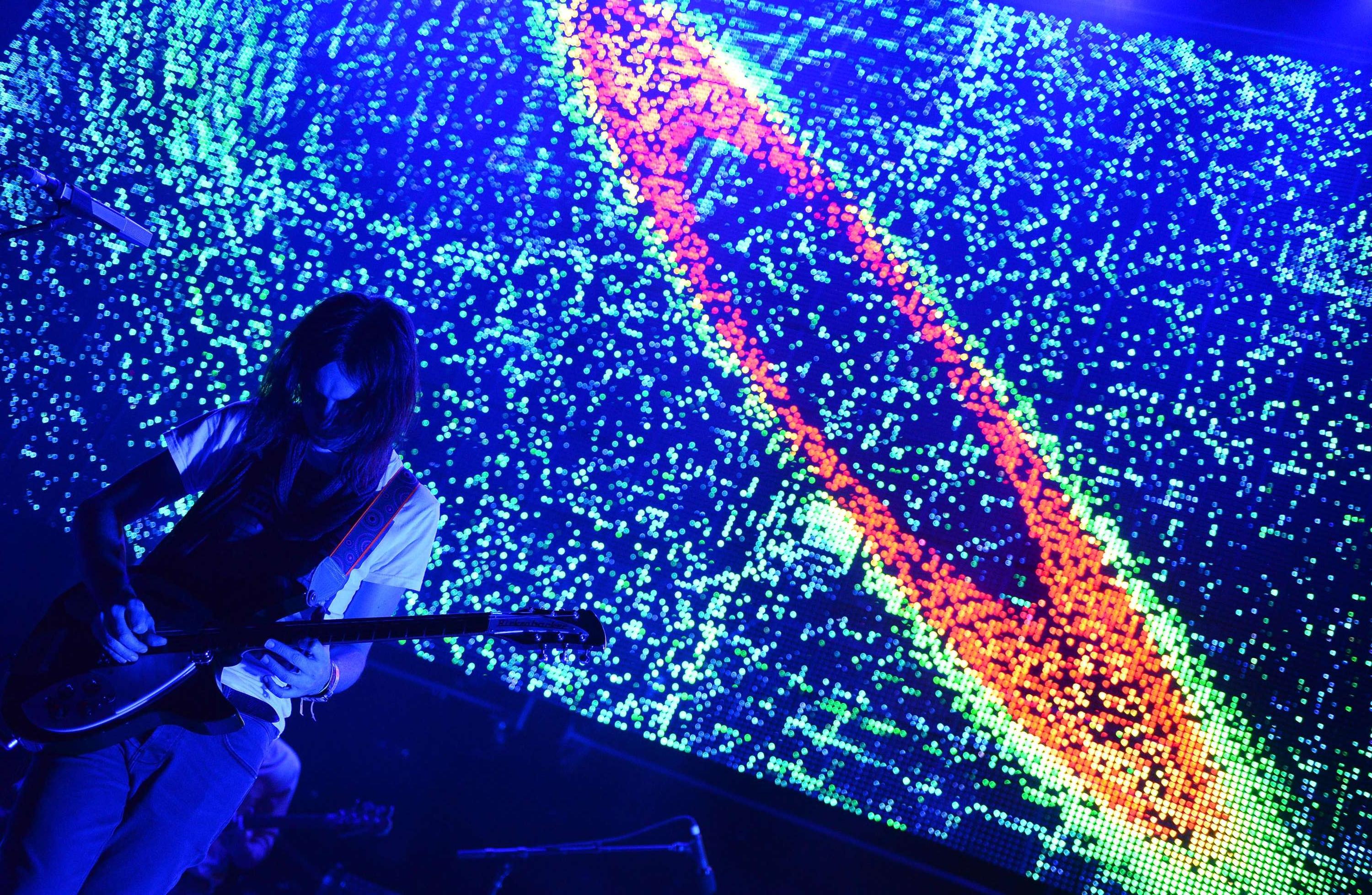

Kevin Nixon / Prog / Future / Getty – Desire Be Desire Show

Tame Impala plays the O2 Brixton Academy in London on Oct. 30, 2012, backed by a projection of Parker’s jury rigged oscilloscope.

So, how does a band from Australia’s most remote city break big? Because artists rarely take openers Down Under, coveted support slots can prove pivotal for rising Aussie acts. In December 2008, Tame Impala landed such a booking, opening for MGMT, another band of internet-era psych-rockers, whose 2007 debut LP, Oracular Spectacular, had proven as popular in Australia as it had elsewhere.

“That was the support that, if we wanted to do a support, that’s what we would want to do,” Regan says.

By then, Modular Recordings A&R exec Glen Goetze had discovered Tame Impala on Myspace, leading the label to release the band’s self-titled EP in October 2008. According to Regan, MGMT and Tame Impala “hit it off immediately” during the brief Aussie tour. More importantly, MGMT brought Tame’s EP back to U.S., and got it into the hands of their agent at the time, Paradigm’s Heather Kolker.

A little over a year later, as MGMT was ramping up to promote their second album, 2010’s Congratulations, Kolker contacted Regan: Could Tame Impala open for MGMT in America?

Tame Impala, which was gearing up to release its debut album Innerspeaker in late May, just a few weeks after Congratulations, was in. As Regan tells it, Tame Impala played a release show at Perth-area theater Metropolis Fremantle, headed back to her place, downed some tequila shots, hopped on a plane to Los Angeles, drove up the California coast to San Luis Obispo and played their first U.S. opening gig for MGMT that night.

“Things look good on paper, and when you have to do them in real life, they’re not the same,” Regan says with a laugh.

As Tame Impala introduced themselves to American fans – from a stormy show at Red Rocks opening for Janelle Monáe and MGMT to buzzy club gigs of its own at Manhattan’s Pianos and L.A.’s Silver Lake Lounge – the band met lean times on the road, with Parker and Regan both learning the live industry on the fly. But audiences quickly gravitated to them.

“When you come from somewhere really far away, and the fans know that, they really appreciate what it takes for you to get there,” Regan says. “They become really loyal.”

Mark Davis / Getty – Psychedelic Start

Tame Impala performs during a co-headlining show with The Flaming Lips at Los Angeles’ Greek Theatre on Oct. 29, 2013.

By April 2011, Tame Impala was headlining sizable clubs, like Manhattan’s Webster Hall and San Francisco’s Fillmore. Kolker was in the process of leaving Paradigm and handed Tame’s reins to French, then also at the agency, who led the band to even larger rooms.

“It was just this progression that never slowed down,” French says. “I didn’t ever feel the need to go open for anybody, because we were ready for the next step after each tour.”

The ticket sales were immediate, but Parker’s acclimation to bigger stages wasn’t.

“There were people that kind of overdid it [with production in Perth],” he says. “We always scoffed at that mentality – which is why I guess it took me a long time to embrace being a performer on a large stage.”

In fact, Parker says he found the industry’s tendency to sand the edges off creativity so intimidating – “They will just put you in boxes; it’s so easy to end up with something so generic,” he says – that he almost quit touring.

“I started telling people we weren’t going to tour live anymore,” he says. “I actually said to everyone, ‘This is it. Tame Impala’s not a live thing anymore.’”

Cooler heads prevailed, and as Parker assembled Tame’s sophomore album, 2012’s Lonerism, he began to conceive a live show to complement his music’s expansive headiness. Tame Impala’s main visual attraction became an oscilloscope, a piece of equipment typically used in laboratories that Parker repurposed for the stage, jury rigging the device so its wave readouts would respond to musical inputs.

“I watch shows now with that oscilloscope, the big green blob going behind us, and I’m like, ‘How did anyone put up with watching that for an entire show?,’” he reminisces with a sigh.

Plenty did. The oscilloscope accompanied Parker as the stages Tame Impala played grew, providing a classically psychedelic backdrop with a modern flair. More new fans flocked to see Tame Impala after the October 2012 release of Lonerism, which received rave reviews and expanded Parker’s sonic and lyrical scope. Live Versions, recorded at a sold-out October 2013 show at Chicago’s Riviera Theatre, documented the band’s growth into a formidable live act.

That fall, Tame Impala co-headlined a tour with The Flaming Lips, a major creative inspiration for Parker and another band that adapted psych-rock for younger generations.

“They made me realize that you can make it your own,” Parker says. “They made me realize that the stage isn’t a rigid structure that you have to use things the way they’re meant to be used. It opened my mind.”

Rick Kern / WireImage / Getty – Instant Confetti

Tame Impala’s dazzling production, including bursts of technicolor confetti, have become a defining aspect of their concerts.

As Parker prepped his third album, Currents, his team sensed it would be a smash. But it went far beyond merely cementing Tame Impala as one of indie-rock’s premiere acts.

“Everything started going really gangbusters from there,” French says. “The sound changed, and it went more in a synth-y dance direction. They kept their psych-rock sensibilities, but it just opened up a much broader fan base for the band. They weren’t just considered a psych-rock band – they were something for everyone.”

Tame Impala went from selling out rooms such as Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium and Chicago’s Riviera Theatre in spring 2015, ahead of Currents’ July release, to filling New York City’s Radio City Music Hall – 5,723 tickets – in October. New Yorkers couldn’t get enough: The night after Radio City, Tame Impala sold out the 2,800-cap Terminal 5.

Parker’s other musical activities bolstered the band’s profile. In 2014, he reworked Lonerism’s “Feels Like It Only Go Backwards” with Kendrick Lamar for the “Divergent” soundtrack; in early 2015, he guested on two songs off Mark Ronson’s LP Uptown Special.

Then came Rihanna. In January 2016, she released her acclaimed album ANTI, and it featured a faithful cover of Currents’ titanic closer “New Person, Same Old Mistakes,” introducing Tame Impala to a vast pop music audience. Come September, Lady Gaga released “Perfect Illusion,” produced by Parker, Ronson and BloodPop. The track hit No. 15 on Billboard’s Hot 100.

Ever the road warrior, Parker continued touring. In summer 2016, he headlined smaller fests like Toronto’s Bestival and Los Angeles’ FYF Fest, and notched hard-ticket successes with sold-out two-night stands at Brooklyn’s Prospect Park Bandshell and the Greek Theatre in Berkeley, Calif. Days after the Berkeley shows, Tame Impala sold 20,609 tickets – still their highest single-show figure – at Mexico City’s Palacio de los Deportes.

The ascent surprised even Parker.

“As the venues we’ve been playing have been getting bigger, I feel like we’ve always been one step behind,” he says. “Every time we’ve moved up a size, I’ve been just getting comfortable playing as big as the last place.”

Tame Impala’s production grew to meet the moment. Parker had long wanted to use confetti during his show’s most climatic moments, and, around this time, he finally quashed the naysaying voice in the back of his head.

“Shut the fuck up, Kevin,” he remembers telling himself. “The music’s good enough. Just do the confetti, Kevin. You know you want to.”

“We have a lot of conversations about confetti,” French says. “There’s certain parks where these festivals are held around the world where the cities will not allow confetti. Once in a while, we have to be like, ‘This is the best place for you in the market, it’s going to be amazing, you’re headlining this festival – but you can’t use the confetti.’”

Rick Kern / Wire Image / Getty – Borderlines

Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker performs during the band’s Float Fest headlining set in Martindale, Texas, on July 22, 2018.

The case for Tame Impala as a major festival headliner had reached critical mass. In January 2017, New York City’s Panorama Festival, presented by Goldenvoice, announced the band would headline its second edition along with Frank Ocean and Nine Inch Nails.

“Goldenvoice, they always really, really believed in Tame Impala,” Regan says. “They almost always put us a slot above where we thought we were going to be on a festival.”

Tame Impala was off-cycle, but taking the gig was a no-brainer.

“We’re punching above our weight here, but we can do this,” Regan recalls thinking. “The thing about Kevin is he loves a challenge.”

Up to that point, Parker had kept production in-house, conceptualizing Tame staples from the oscilloscope to the confetti himself. For Panorama, he recruited outside help. Willo Perron and Rob Sinclair came aboard, rounding out the sensory experience with state-of-the-art lasers and immersive video screens.

Parker was still “very personally involved – he’d even programmed lights using MIDI commands,” Sinclair, a partner at Sinclair / Wilkinson who still serves as Tame Impala’s production designer, tells Pollstar by email. “I think he realized he needed some help to take the show onwards, but was also nervous about losing control. I think we managed to strike the right balance and show him that a supportive team could help him build appropriate environments for his songs and amplify, rather than replace, his vision.”

“You have to put on a show equivalent to what you’re getting paid,” Regan says. “When we got offered that show, we didn’t take it lightly. We knew it was a big deal.”

So did the audience. When Regan got back to her hotel after the set, she received a Google alert: “Tame Impala prove why they’re a festival headliner.”

“We’ve never looked back,” she says.

Timothy Norris / Getty / Coachella – Indio Impala

Tame Impala headlines Coachella on April 20, 2019, culminating the band’s ascent to the top of the festival world.

As Currents celebrated its third birthday in July 2018, speculation about its follow-up grew. That summer, Tame Impala headlined a handful of festivals, including Chicago’s Pitchfork, and Parker contributed to Travis Scott’s album Astroworld, later joining the rapper on “Saturday Night Live” in October as part of a backing band that also included John Mayer.

Shortly after, Goldenvoice offered Tame Impala a Coachella subheadliner slot. Regan declined; Tame Impala had occupied the same slot in 2015, before Currents’ release. An unexpected development validated her decision. In October, vocal cord bruising forced Justin Timberlake, reportedly set for Coachella 2019, to postpone shows. Though the pop star ultimately returned to the stage that spring, he had to pull out of Coachella.

Coachella needed a new headliner, and Tame Impala was Goldenvoice’s chosen replacement. But Parker hadn’t finished his new album. In November 2018, a day into sessions for it, fires destroyed the Malibu house where he was recording. Parker, his hard drive and the bass he’s written every Tame Impala song on escaped; $30,000 of equipment didn’t, according to the New York Times. An album wouldn’t be ready in time.

“Kevin Parker would never let anything out of his hands until it was perfect,” says Regan, but “we would never headline without new music.” Tame Impala played two fresh singles, “Patience” and “Borderline,” on “Saturday Night Live” in late March; the following month, it hit Coachella.

In Indio, Parker debuted Tame’s latest stage innovation, a massive ring of lights that hovered above the stage, moving and flashing like a UFO, which Perron designed as “a grand gesture,” according to Sinclair.

Tame’s set, wedged between headlining turns by Childish Gambino and Ariana Grande, solidified the band as a top-tier festival headliner. Bill-topping gigs at Shaky Knees, Boston Calling, Lollapalooza, Osheaga and Austin City Limits followed that summer. Overseas, Tame Impala headlined Glastonbury’s Other Stage.

“Tame Impala appeals to a broad audience – not just psych-rock fans, but multi-genres like hip hop, electronic and R&B,” C3 promoter Amy Corbin, who oversees ACL, told Pollstar by email. “Their festival performances are sonically and visually stunning and take you on a musical journey. This is exactly what makes a festival headliner memorable.”

French and Regan booked gigs around festivals when possible, with Tame Impala moving thousands of tickets headlining in markets from Toronto to Asheville, N.C. New York, meanwhile, remained a leading indicator. In August, Tame moved 24,164 tickets and grossed $1.32 million over two sold-out Madison Square Garden shows.

“I remember standing in the middle of Madison Square Garden watching some of the show,” says MSG Live executive vice president Darren Pfeffer. “Tame Impala’s circular truss of lights, lasers and all the effects with the way they use their screens, it really pulled the audience in together. It felt very intimate. They really connected with the audience.”

“We did have a big year of touring, which actually turned out amazingly well for the actual album setup,” Regan says. “It was backwards, but it worked really well.”

Daniel Knighton / Getty – Yes I’m Pechanging

Tame Impala’s 2020 arena tour kicks off at San Diego’s Pechanga Arena on March 9, 2020.

After The Slow Rush finally arrived in February, Tame Impala hit the road with a refreshed show in early March.

“We talked about what elements were disposable and what were part of the Tame Impala DNA,” Sinclair says. “We decided to make all new video content, change the stage layout and keep the ring, but see if it could do some new tricks.”

The ensuing design introduced bigger and more precise lights and screens, and retooled the ring – now “Ring 3.0,” per Sinclair – with better motion control, additional lighting and smoke-spitting capabilities.

The changes extended to the setlist, where longtime staples like “Mind Mischief” and “Why Won’t You Make Up Your Mind?” were booted in favor of several disco-tinged Slow Rush songs – and, curiously, “Expectation,” an Innerspeaker deep cut Parker hadn’t played live since 2011. (“It seemed like the right song to play at the right time,” Parker says coyly.)

Dates were predominantly arenas across the continent, with festival headlining turns (Bonnaroo, Governors Ball) and even a stadium gig at Mexico City’s Foro Sol sprinkled in.

“It was really important that we put a straight-up headline tour up around North America this time – not just playing festivals – and go out there and actually sell hard tickets and do an arena tour around this album,” French says. “They really hadn’t done that.”

Parker denies tailoring The Slow Rush to fit the band’s increasingly big gigs – “A lot of these songs I imagined performing in a club,” he says – but acknowledges its grandiosity.

“Some of the songs on this album are my most arena-friendly rock,” he says with a chuckle. “I say that in the most endearing way. I say that both in a Spinal Tap way and a genuine way.”

For the first time, Parker explains, he finally felt like Tame Impala’s level of experience corresponded to the rooms it was booked to play.

“This tour was the first tour where I’ve been, like, ready for it mentally,” he says. “Like, ‘Alright, let’s fucking do it.”

Promoters shared Parker’s enthusiasm.

“Tame Impala had long been on our dream list to play the Forum, and Los Angeles has always been such a strong market for them that it is something that could have happened prior to 2020,” the Forum’s Lincoln says.

The trek started at San Diego’s Pechanga Arena, where Tame Impala moved 10,304 tickets and grossed $704,625. And, save for the live industry’s looming shutdown, the Forum shows went off without a hitch.

“Looking back now, Panorama was terrifyingly seat of the pants,” Sinclair says. “It’s been getting better ever since.”

“These shows were beyond expectations on the production level,” Lincoln says. “What Tame Impala did to coordinate their music with the live production elements made it visually one of the greatest shows we have had the pleasure of hosting.”

But, to paraphrase an old Tame song, it was not meant to be. Dates were falling off the band’s itinerary. Crew members were worried about getting home safely in the event of pandemic-related travel restrictions.

“Every day that passed, the gravity of the situation got greater,” Parker says. “By the time we called the tour off, it was so obvious. The world had plunged into this new era. I forgot all about the tour.”

Venla Shalin / Redferns / Getty – Past Light

Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker strikes a pose at London’s O2 Arena on June 8, 2019

Parker and Regan are now holed up where it all began in Perth, and they sound almost of another dimension. In Australia, handshakes have returned. So have concerts, for that matter. Parker’s upbeat about the future – Tame Impala’s, live music’s, the world’s.

“Shaking hands was outlawed socially – and actually,” he says. “There was the elbow bump. But we’ve basically eradicated coronavirus in Perth; we haven’t had it for months, had a single case. People were like, ‘Are people going to go back to shaking hands? Because that feels really gross at the moment.’ Back in Perth, as soon as everything was safe, everyone just sort of clicked back to how they were. People will shake hands now. People will hug.”

In quarantine, Parker’s remained active, filming high-concept performances – no livestreaming, for now – including a spot for a September appearance on Jimmy Fallon’s show recorded at Metropolis Fremantle, where Tame Impala played its Innerspeaker release gig before heading to the States in 2010.

“I wasn’t really sad for the tour getting called off, until weeks later, when I suddenly went like, ‘Oh, shit, that’s right. We started a tour. We did all this work,’” Parker says.

The North American dates have been rebooked, resuming in July 2021 with the tabled Foro Sol show, then hitting arenas and festivals including San Francisco’s Outside Lands and Las Vegas’ Life Is Beautiful. Parker can’t wait to resume touring, warts and all.

“Soundcheck is gonna be fun,” he says. “Trying to get to sleep on a tour bus that’s rattling around on the highway and I’m a little bit drunk is going to be really fun. Waking up with a hangover on a tour bus feeling like I need to vomit, but I can’t, because someone’s in the toilet and we’re still three hours out from the next city is gonna be really fun.”

Parker’s ascended to the music industry’s highest echelons – as a rock act in 2020, no less – but he’s still less interested in the where than the what.

“Put me in a shed with all the same people and I’ll be happy,” he says. “Put me in a field, you know?”

Daily Pulse

Subscribe

Daily Pulse

Subscribe