Features

Author Robert Greenfield On Bill Graham’s 90th Birthday: ‘He Never Would Have Sat In A Board Meeting’

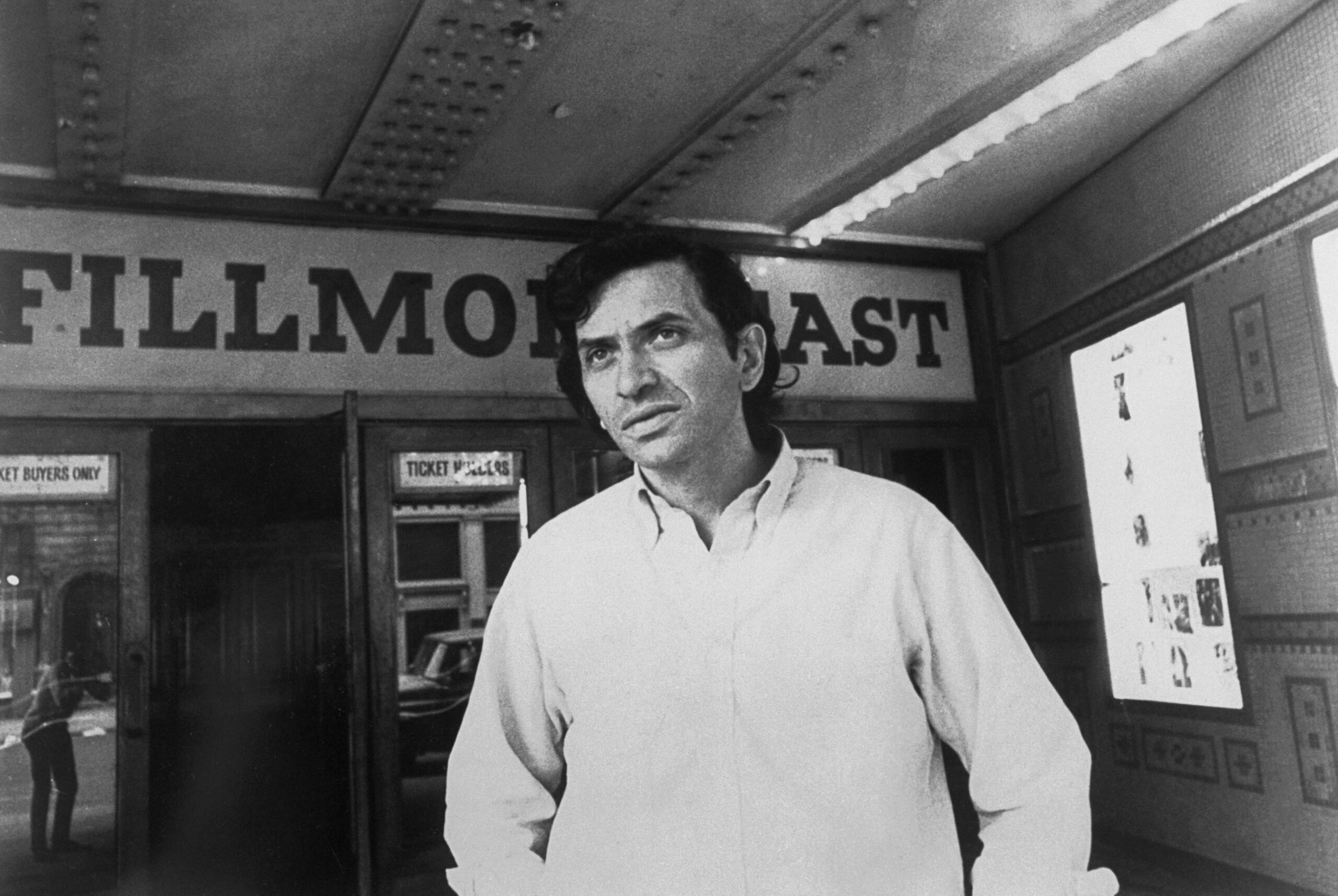

(Bettmann /Getty) –

The Trail Blazer: Bill Graham circa 1971 outside New York City’s Fillmore East which, along with the Fillmore West, helped set the bar for what live music clubs could be.

This oral history includes recitations and revelations from a cavalcade of music legends, including rock stars (Keith Richards, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Robert Plant, Pete Townshend, Grace Slick, Robbie Robertson and Eric Clapton among others) executive luminaries (including Frank Barsalona, Elliot Roberts, Peter Rudge, Jon Landau, Rock Scully, Dee Anthony, Bill Thompson, Phil Walden, Dell Furano, Harvey Goldsmith among others) and paragons of the counter-culture (Ken Kesey, Owsley Stanley, Wavy Gravy, Joshua White and Wes Wilson).

Here, Greenfield, who is currently working on a book on playwright and actor Sam Shepard, helps put Graham’s legacy into perspective, breaks down what drove the great promoter, discusses the dissolution of the Fillmore East and what Graham would have made of today’s more corporate live business (hint: “He would have hated it!”).

–

Pollstar: This is one of the best books I’ve ever read.

Robert Greenfield: Oh man, thank you so much. I appreciate that.

Bill Graham’s story is just incredible and epic.

It’s incredible. What’s interesting in retrospect, and I can’t believe he’s been dead for 30 years, he died in ‘91, is that in the time frame that he was with us, and I lived through all this and it’s kind of heartbreaking, is that nobody understood why he was so angry. Everybody’s like “What’s wrong with Bill? Why’s he yelling all the time? What is with this guy?” The anger came from his life, right?

But defining him through anger would seem to just scratch the surface…

Right, but that’s what a lot of people saw. And you have to remember in the hippie days, this was so inappropriate. Like, “Dude, calm down,” you know what I mean? (laughs).

Well especially San Francisco, coming from the Bronx and being a New York Jew who was blunt and brash, it wasn’t the San Francisco way.

No, it was a clash, definitely a culture clash. But he loved it out there. He did live in both places. He was the purest New York product of all time. Immigrants adapt to culture in a way that often people born into it don’t. They learn about where they’re living by learning from street culture and popular culture. That’s Bill going to the Park Plaza movie theater and learning from John Garfield what it’s like to be American. But back in those days, the difference between New York and San Francisco was incomprehensible. They were different planets.

What was your role as co-author?

It was such a mad time and Bill had crazy people around him. They wanted Alex Haley to do his book.

It’s funny you say that because the book reminds me of an epic history like “Roots” or “Malcolm X.”

Well that’s very cool, thank you. It was a slow build. I first interviewed Bill for “S.T.P.: A Journey through America With The Rolling Stones,” my first book. Up until then I had been at Fillmore East every weekend for a year and a half. And I’d go to Fillmore West; Fillmore Auditorium was closed already. I grew up with guys like Bill, yelling and screaming in Brooklyn, so I wasn’t a great fan when I interviewed him for the Stones book. He was hysterically funny and I got it because I also worked in the Catskills. So I got him on that level and had a different connection with him. Then a great friend of mine – Jerry Pompili, who I met on the Stones’ “Goodbye Great Britain Tour,” when they left England in March of ’70 and then we were surviving in the South of France together when I was living at Villa Nellcôte for the Keith Richards interviews – he was my connection to Bill. And Jerry kept pushing me forward like, “Hey Bill, it’s Bob.” And he would look at me like, “Who the fuck are you?” “Hey, say hello to Bob.” And then I talked to him.

Basically they brought me in to write the book. I always wanted it to be an autobiography because I wanted everybody to tell his story. I wanted it to be like when they were arguing in the dressing room before, after, and during the show. That was rock and roll. And because Bill wrote the letter, “Hey, this guy is writing my biography” and he still was so powerful and they all needed him, I flew to England and did 120 interviews for the book. That’s why Pete Townshend and Clapton and Bob Geldof and the whole panoply of the English rock royalty, as well as everybody else is in there. I talked to Grace (Slick) and Paul Kantner and Carlos (Santana).

How many years did it take to write?

I showed him the book before he passed away. I went to his last birthday, he celebrated it in Telluride, where he had a house. I showed him the book and he hated it, hated it, yelling at me. The only argument we ever had. I didn’t argue with him. You didn’t argue with Bill. But at that point I probably spent two and a half, three years. The original contract would have been signed in ‘88. He was – a big surprise – impossible to work with. He would not take any time off from the office, couldn’t stop working and would only talk to me on the weekends. We spoke for hours and hours. When he read the book – and of course, I understood everything in retrospect – he was saying things to me like, “I don’t say, ‘is not.’ I say, ‘ain’t.’” Why was he flipping out? I’ve done so many of these since. Especially someone like Bill, when they read the book with their life story, they flip out because, “Oh, does this mean I’m dead now? Is this it?” A couple of weeks later he called me and we laughed. I just said, “Bill, why? I mean, you said all this. I didn’t make any of this up. This is from the tape.” The book would have come out in any event, but it would not have been under my name. I only had to come in as a speaker after he was gone in order to organize the material and give perspective on it. I had to write about the final concert for him. It was astonishing. There were a quarter of a million people in Golden Gate Park for a rock and roll promoter. It’ll never happen again.

He doesn’t really come off that mean in the book, he often just cuts to the chase.

So here’s the other thing. Bill wanted to be an actor, he was an actor. So much of it, the public anger, so much of it was an act. Have you seen “The Last Days of the Fillmore” movie? There’s a scene where Bill is screaming on the phone like, “You’re fucked!” but there was no one on the other end of the phone. (laughs).

How do you think the San Francisco scene, specifically its particular and peculiar ethos of drugs, community, sharing and money’s not the only goal in life, this sort of utopian ideal, influenced him?

He learned from it. And the Grateful Dead turned him on to acid. You read that, right?

(Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images) –

Grateful Dead, from left, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, Bill Kreutzman and Bob Weir perform at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco in early summer, 1967.

The 7-Up cans. They were after him for a year. I think it helped save his life because he saw another way of coping with hard reality. He saw the bullshit, he saw through a lot of these people, not so much in San Francisco, but the ones who took over — he knew who was real and who wasn’t. He knew Kesey was real. He knew Garcia was real. He and Jerry, they loved each other. I went and talked to Mountain Girl, (Carolyn Garcia), Mountain Girl loved him. You can’t get further from Bill Graham than Mountain Girl and Jerry. And the Dead loved him. They got it. So there was a a cross-culturalization. After what he’d come from, after you fought in Korea and now you’re in the Haight in 1967, and you’re open enough to not just put these people on stage, but to actually listen to what they’re saying and realize that to oppose the war like he did, to step up against Reagan, the fact that he was open enough, that he got the message—it made him better at what he did because he opened up to the understanding that you’ve got to take care of people.

It’s really impressive the way he adapted to the music, spotted young talent, and gunned for them. I mean he was talking to Hendrix between shows and was underwhelmed and basically told him he was phoning it in–who tells Hendrix that?

Between the shows at Fillmore East, he said to him “you did everything but play, motherfucker.” And Hendrix went out for the second show and he didn’t move. And you know how great he was, he just stood there and played and he said, “What do you think? Fuck you, Bill” Bill had an effect.

Right, it was, “Tell me what you think.” And so he did. I can’t explain this aspect of it, but he knew which comedian was funny. He knew who the great actors were. He had taste. That’s the point. He had taste in music, even if he didn’t like the music personally.

And he wasn’t bound by genre. It could be the Allman Brothers or Hendrix or Miles or the Sex Pistols. Whatever he liked and was hot.

I saw the Pistols the last time they performed live. I would say a lot of it has to do with the fact of when he grew up, that era, Frank Sinatra, big band music. Then he does the outlier thing and starts dancing Latin. And then he gets into jazz because he lives in The Village– I mean he goes to Miles’ house.

I know!

Miles hasn’t left his fucking house in seven years, and Miles’s smacked out and crazy and Bill begs him to come play. And Miles is putting him through the test, the dozens, and says to Bill like, “Okay, man, you tell me. You know Jazz, who’s your favorite female vocalist?” And Bill says, “Carmen McRae.” Well, that’s the end of that conversation, you know what I mean? Like if you’re in as much pain as he always was, anything or anyone that allows you to escape, you revere. And that’s what movies were. That’s what music was. And so if you prize art, artists notice. They feel it. They get it. So that’s my best answer.

(Photo by Richard McCaffrey/Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images) –

The Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious, Johnny Rotten and Steve Jones perform live at The Winterland Ballroom, a show promoted by Bill Graham on Jan. 14 1978 in San Francisco.

Oh, my God. That was one of the most extraordinary events I’ve ever been to in my life. And I’ve been to a few shows. It was like the Armory Show. It was a departure from everything that had come before. I sat behind the stage with my wife. People were throwing pennies and spitting on the stage. And Sid Vicious was out of his fucking mind. And Johnny Rotten, not my favorite guy. It wasn’t a question that was like, “Oh, did you like the music, Bob?” No, it wasn’t about that. And Bill was crouched behind the amps. And him and Malcolm McLaren, let me not speak ill of the dead. But okay, fine. Bill was transfixed. I have a photo that my wife took. Bill is kneeling behind the amp staring at this. I had been in England and seen new wave, and we’d seen punk. And we knew people who were doing it. We knew guys at Stiff Records. So we had a background. But seeing The VOM open for them, Richard Meltzer’s band, I’m telling you, man. It was at Winterland, 5,000 people, big venue, it was an extraordinary evening.

it’s so smart that he knew punk was coming and just jumped on them.

He put them on. That was a very small tour. They played like six or seven gigs for nothing,. They weren’t on a massive tour, and how and why they came– it was Bill.

They didn’t really play much more after that, I think it all fell apart.

Winterland was the last gig.

But he wasn’t even into rock and roll in the beginning.

Bill was one of the first people who saw rock music as art and an art form. There’s a reference to this guy who promoted the Chicago Arena, which was a pit of major proportions, with a hat and a cigar. The Four Seasons would perform through the ice hockey arena sound system PA. There were no fucking amps. It was like, “Give the kids a Christmas show, Murray the K. Give them an Easter show. Alan Freed. Have them in, have them out, get the money, fuck them, they’re just kids.” Bill got it. When he saw Jim Morrison, he got it. He treated the musicians like artists. He treated the people who came to see the musicians like they were at Lincoln Center. That was one of the revolutionary things he did. He created the modern rock concert. Those lights, that sound. I moderated a panel at the New York Historical Society last February. There was a Bill Graham exhibition out there. All these people from Fillmore East were on the stage. We had 400 people there who left knowing they would have given their eyes and teeth to have been at Fillmore East because it was the height. Fillmore West had great music, but it was hippies. Nobody looked at the stage, it was wonderful. Fillmore East was New York. Pressure’s on, best light show ever, best sound system ever.

But look what he survived as a kid and look at the radar he had. Bill had the quickest street sense of if this guy’s dangerous, this guy’s cool. He could suss you out in seconds. Plus, look at Korea in combat. But having said that, he was the least physically violent person I have ever known. Never raised a hand, never hit anybody.

And unafraid to stand up to people. It seemed like he could talk his way out of any situation with the cops, the Hell’s Angels, whomever. He even got slashed in the face with a chain by a Hell’s Angel.

(Photo by Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images) –

Duane Allman of The Allman Brothers Band performing on the last night of Bill Graham’s Fillmore East, oJune 27, 1971.

One of the shocking things in the book is when he decides to sells the Fillmore East and says artists are charging too much and they want to play Madison Square Garden. And no less a figure than Frank Barsalona said, “Don’t do this, Bill!” Venues have a point where they tap into a zeitgeist and everyone goes there, like Ahmet Ertegun, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, Clive Davis – like the Fillmore was a club house or a Soho House or something. And to unplug that and be like, “I’m done,” seemed like the worst timing. And the book didn’t really explain it well.

So June Barsalona came to the event and I talked about Frank on stage because I interviewed him, he was a massive figure. Frank was a businessman. Bill was an artist.

And a businessman.

And a businessman. He burned himself out with the flying back and forth every weekend to the Fillmore East, which was not that easy back then. He was frustrated. He felt like he was being mistreated. It’s not easy to understand because we’re not Bill. It wasn’t a rational decision. He had plenty of money already by that point. It was not about the money, it was the money, as Bill would have said. And he came back and he took off. He went away and he came back and he was bigger than ever.

Would the Fillmore East have continued?

Oh, my God. For another 10 years.

How long was the Fillmore East around for, two or three years?

Yes, exactly.

And Miles Davis, Cream, Hendrix, The Allman Brothers…

I saw Miles open for Neil Young and Crazy Horse. It was incredible. It was just such a great scene and it was Bill. Bill had this musical taste. Bill wanted you to see B.B. King or Otis Redding.

It’s amazing. Yeah.

Did he regret selling the Fillmore?

His political activism is also really impressive, too. I know he was involved with Bob Geldof, Amnesty International, Live Aid, the schools in San Francisco, and he wrote an open letter to Ronald Reagan about his Bitburg cemetery visit and spoke at a protest in Union Square and subsequently they burned down his office.

Correct. They firebombed his office.

And when asked, “Are you going to go after these fuckers he said, “No.”

No. He said no.

And all these people like Jerry Pompili wanted to go after them.

He had the guys, they had guns. He had fucking guys who would put out the word. Go to the East Bay, go to these bars, put down money, find these guys. They wouldn’t kill them. They would have just brought them to the cops.

What was the justification for not going after those guys?

It’s the justification people are now talking about and not impeaching Trump again. You’re going to create more anger, more hatred, more repercussions. We’re there right now. He just didn’t have the heart to continue the fight.

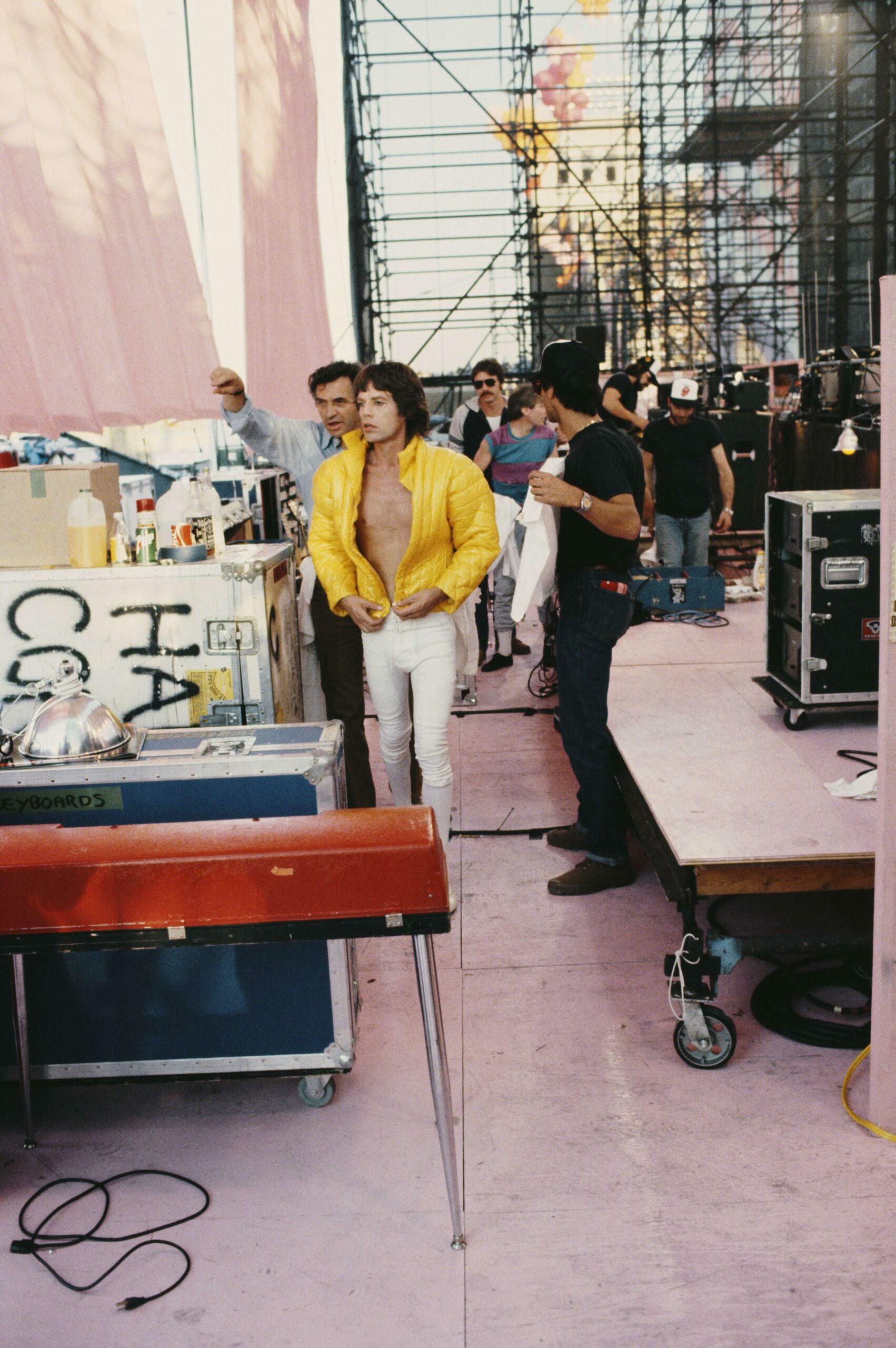

(Photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images) –

Mick Jagger backstage with Bill Graham at John F Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia on the first date of the band’s U.S. Tour, which Graham promoted, on Sept. 25, 1981.

What do you think he would have made of this time out we’re having and this civilizational throw-up we’re going through?

I don’t know. The virtual thing would not have been a substitute for what he lived for. What he lived for was the interaction between the artist and the audience. And what he was a genius at, and this is really off the hook here, but it kind of relates to what they did at the Capitol. Bill was a genius at this. “I got 100,000 people, how do I get them in? And then once I get them in, how do I get them out? How do I make sure nobody gets hurt? This is a crazy fucking show. How many security guys am I going to have backstage? Am I going to let them come in the front or do I bring them in the back?” He was obsessed, and he was a genius at this.

He set up medical personnel at the stadium shows.

And he had the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic. David Smith. He always had medical people there. But it was more than that. He was always thinking about, “Oh, we should have water. Oh, we should allow them to be able to get out of the sun. He was obsessed on a level that spoke to this is what he cared most about in the world.

What’s so interesting about the live business and what I love about this business is that Bill and so many others have so many skill sets and are Jacks of all trades, and can do anything. Like when the pandemic hit, suddenly live companies were making face shields and transporting food to those in need and doing political advocacy.

Oh, he would have done that. He would not have sat back. He would have been out there. He would have been distributing food, and he would have been in San Francisco and or New York. He would have involved himself, both by raising money and doing the stuff you’re talking about.

And here on what would have been his 90th birthday, what do you think he would make of the live business today?

Here’s the most fascinating thing about Bill and one the most substantive things: he raised more money for good causes through rock ’n’ roll than anybody who ever lived. He brought the concept of charity into rock ’n’ roll and it then got widely adopted. All these people he trained, they remained in the business after he passed away. The company continued. If you go to a show at the Fillmore Auditorium, there’s this moment before the band comes down where the lights above go purple, and it’s just the way it was in 1965. It’s so moving and stunning. Bill would have hated the business as it is now. I can’t imagine him at 90. I was thinking about this. That doesn’t mean he couldn’t have been 90. Who knows? It’s just hard to know. I mean, we’re talking about the business at a moment when it doesn’t exist anymore, right?

He missed the whole consolidation of the business.

Thank God. He would have hated it

Would he have hated that or would he have become part of it?

Do you think he would have been a CEO or SVP at Live Nation or AEG today?

Well, Another Planet are his people, Sherry (Wasserman) and Gregg (Perloff), I’ve known them forever.

He would have loved Outside Lands in Golden Gate Park. He would have adored that. He would have taken over Hardly Strictly and booked that every year. I mean, again I have never thought about this but Gregg and Sherry would have worked with him in a heartbeat, he could have been the head of Another Planet. He could never have retired. This I know. It’s not possible.