Features

Michael Lang, The Face of Woodstock, Dead at Age 77

Henry Diltz –

Woodstock co-founder Michael Lang rides a BSA Victor motorcycle in 1969 at the festival’s Bethel Woods, N.Y. site.

Michael Lang, the original co-creator of 1969’s Woodstock Music & Art Festival and the person most closely associated with the original festival and several of its subsequent anniversary events, has passed away at the age of 77. According to his publicist, he passed away from Non-Hodgkin lymphoma on Saturday (Jan. 8) at New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Don Paulsen / Michael Ochs Archive / Getty Images – Half A Century Ago

Woodstock co-founder Michael Lang, at age 24 in New York on May 23, 1969.

“In 1969, the bands at Woodstock were all part of the counterculture,” Lang told Pollstar when asked in 2019 about the original fest’s legacy. “They were very much involved in our lives. It wasn’t just entertainment; it was more about the social issues. They were part of our generation. Woodstock offered an environment for people to express their better selves, if you will. Give them that, and it seems to work. It was probably the most peaceful event of its kind in history. That was because of expectations and what people wanted to create there.”

Victor Englebert / Photo Researchers History / Getty Images –

David Brown and Carlos Santana perform at Woodstock Music & Art Festival in 1969.

With the motto “Three Days of Peace & Music,” Woodstock is considered a watershed moment culturally and something of a template and cautionary tale for the nascent music festival industry. The hundreds of thousands who attended, in large measure, identified with the late-60s counterculture, which had coalesced around rock and roll writ large, a growing anti-war movement opposing the Vietnam War and draft, the support of civil rights and a loosening of traditional social mores.

The Brown Acid Was Wonderful: A Woodstock 1969 Oral History

At the same time, the original Woodstock, much like subsequent iterations, faced immense production and operational challenges. Settling on the original Woodstock site was something of a fiasco, much like later editions, going from the upstate N.Y. hamlets of Woodstock, Saugerties and Wallkill, which Lang’s team had worked a few months before the town passed a law a month out which made it impossible for the festival to proceed.

“We had a month to put the festival back together and to find a new site,” Lang told Pollstar in August 2019, when his ill-fated 50th anniversary festival faced similar challenges. “We just packed up, I put everybody on the phone making calls to the press and radio stations looking for someone who had a home for us and the next day someone called.”

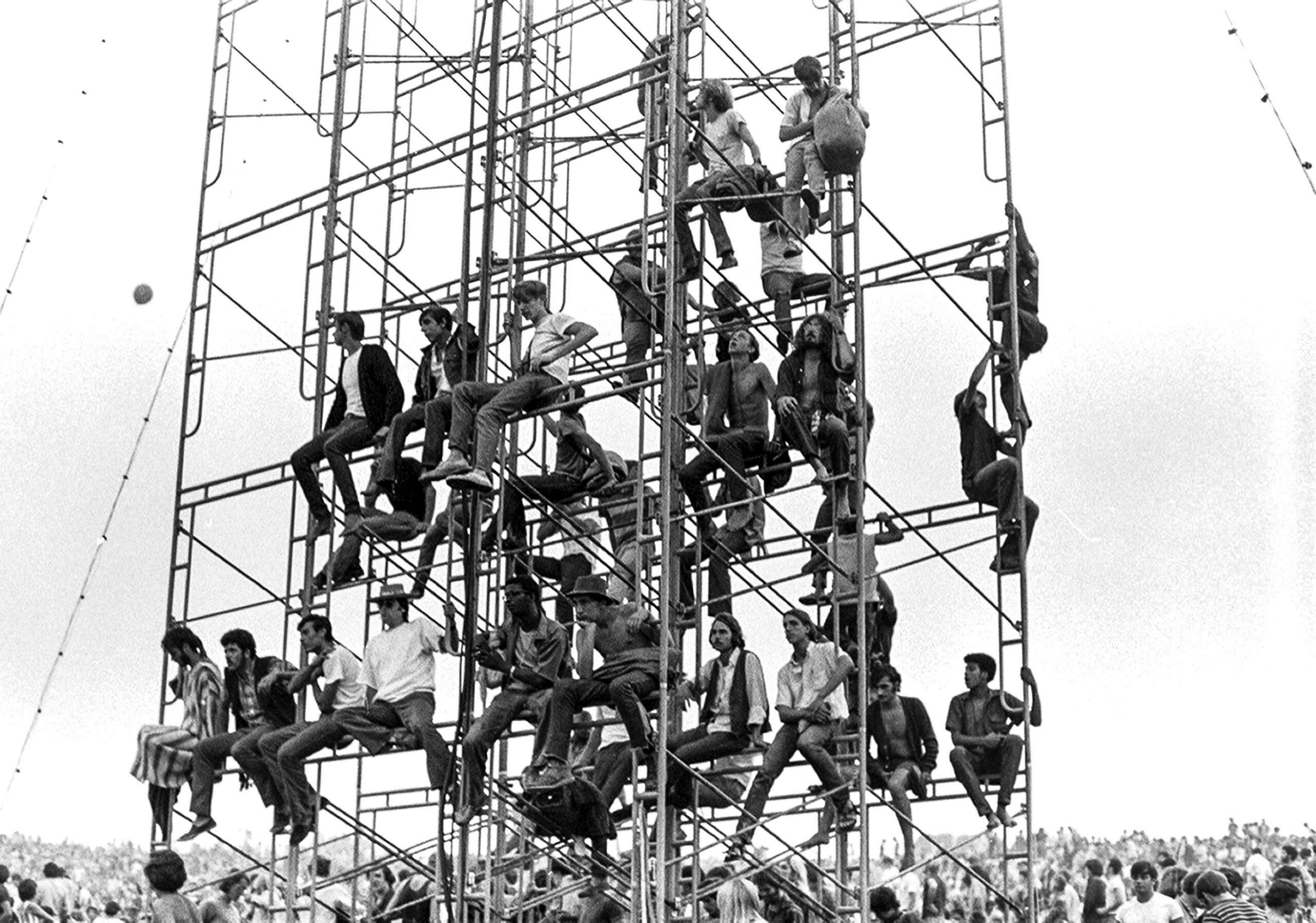

Alvan Meyerowitz / Michael Ochs Archives / Getty –

Fans climb the scaffolding to get a better view at the Woodstock Music & Art Fair at Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in August 1969 near Bethel, N.Y.

That call would lead to Max Yasgur’s 600 acre farm, though it wouldn’t help assuage the massive operational challenges Woodstock faced. This included snarling traffic shutting down the New York Throughway, a lack of fencing that turned the event into a literal free-for-all with no capacity limitations or ticket requirements, inclement weather as well as little if any amenities.

Many of the personnel who oversaw the show’s operations were culled from Bill Graham’s Fillmore East, though Graham himself never got on board. This included John Morris, the fest’s booker and Head of Production, Chris Langhart as tech Director and Chip Monck as lighting designer and master of ceremonies. Having experienced personnel book and produce the performances, along with the subsequent 1970 documentary “Woodstock,” helped enshrine many of the fest’s standout performances and counter-cultural ethos ensuring the event would live on in the popular consciousness.

Woodstock helped frame and distill what was already in the air in 1969. In Michael Lang’s 2009 book “The Road to Woodstock,” festivalgoer Rob Kennedy realized, “I don’t think any of us believed there were that many hippies in the USA. We were the only freaks in our high school at that time. We knew there were some in surrounding towns, but we had no idea. That was one of the most empowering aspects of Woodstock. We realized we had the numbers.” At Woodstock, along with the subsequent documentary, this tribe created something of a moment in time and found their voice, which subsequent editions of Woodstock failed to accomplish.

(Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Woodstock 50) –

Michael Lang during the announcement of Woodstock 50’s line-up at Electric Lady Studio on March 19, 2019 in New York.

Woodstock ’99, produced with Scher and Ossie Kilkenny, was far worse. Held at Griffiss Air Force base in Rome, N.Y., the event faced a host of challenges including proper security, sanitation, water, sweltering heat, crowd management and large distances between stages. These failures led to riots, fires and, most disturbing, sexual assaults. The debacle that was Woodstock ’99 was seen as a betrayal to the original event’s ethos of peace, love and music and perhaps should have been the time to pull the plug on any further anniversary celebrations.

The ‘99 edition’s abject failure influenced Woodstock 50’s inability in 2019 to find and retain venues, sponsors, promoters and artists as various locales declined to host the festival’s 50th anniversary. It’s final ignominious cancellation, after it was slated to play Merriweather Post Pavilion in Columbia, Md., was the event’s final nail.

Lang’s other endeavors included a label, Just Sunshine, which ran in the early- to mid-70s and put out some 30 albums by artists that included Betty Davis, Karen Dalton, Mississippi Fred McDowell and the Voices of East Harlem. It was distributed by Famous Music and Paramount Records. His management clients included Joe Cocker, Rickie Lee Jones and Willy DeVille. He also formed Woodstock Ventures and The Michael Lang Organization, which included live events, management and film production.

Michael Lang’s legacy, depending on who you speak with, may be viewed as a legendary counter-cultural saint or a charlatan exploiting Woodstock’s legacy. Likely, as with most things, the truth is somewhere in between. One of Lang’s greatest gifts it seems, was to soldier on in the face of adversity no matter the critics. When Pollstar last spoke with Lang during Woodstock 50’s inordinate challenges, he was calm, articulate and charismatic amidst the maelstrom, which was his way. “My hair’s not on fire,” he said. “It’s always been kind of my nature that when things get weird, I get calm. But for us there’s a clear path…we’ll just deal with it.”