Features

Why CMA Fest Matters: The Power Of Country Music To Bring The World Together In Nashville

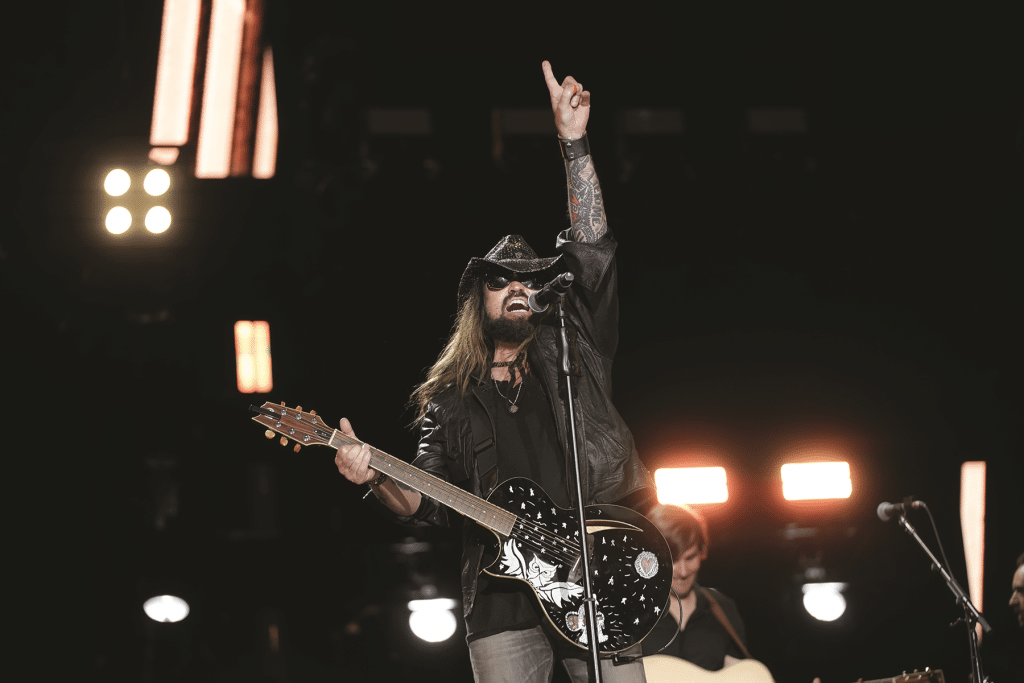

Courtesy of CMA/ABC

In 1972, if you’d told industry leaders Bud Wendell and Jerry Bradley when they hatched a plan to keep the fans away from DJ Week, now Country Radio Seminar, their event would eventually fill Nashville’s football stadium and bring 300,000 people to Nashville, they’d’ve laughed.

Sure, Fan Fair, originally staged at the Municipal Auditorium, could pull off shows for up to 8,000 with a few thousand people up close and personal with their favorite country stars in the basement; but a global festival? Come on!

Even with a move to the Fairgrounds – again to ease gridlock downtown from the onslaught of fans – and the 17,000 it grew to, Fan Fair wouldn’t attract sponsors like Chevrolet, Dr Pepper and Anheuser-Busch, have 10 stages with more than 300 artists playing daily, let alone anchor a major network television special. Indeed, labels were questioning its value as the ‘90s came to an end, actually pressing to make the event go away.

“I remember (then-Sony Music Nashville chairman) Joe Galante telling me when they were trying to shut it down that it was a lot of cost and work, and they didn’t see any return,” says legendary agent Tony Conway, who manages Country Music Hall of Famers

Alabama and Randy Travis. Ultimately, Conway spearheaded saving Fan Fair and moving.

Photo by John Russell / CMA

“The labels paid for everything and the artists played for free… Attendance was starting to fall off, too. I understood.”

Conway joined the Country Music Association board of directors in 1976; immediately he was appointed to the Fan Fair Committee because he knew fairs. He’s witnessed every incarnation of the singular event, recognizing the impact that connection with the fans meant.

Kix Brooks, half of CMHoF inductees Brooks & Dunn, was on the CMA Board when the discussions to kill the event began. He marvels, “[Fan Fair] was a hero zone for artists; you were king of the world. But there were no cell phones, no internet, no social media. At the time, Broadway was really nasty. Robert’s, The Stage, Layla’s and Tootsie’s were happening, but there was so much porn. The stadium was being built, and it felt like maybe there was a larger play here. Tony and I got to talking about Houston Livestock Show & Rodeo, Jazz Fest, and…”

Without a ton of excitement, Conway began lobbying. Individual board members, business leaders, the mayor. No one got it, but as the 20th century turned into the 21st, the tide began turning. With a major stadium – and help from Kitty Moon Emery, who was also on Nashville’s Sports Authority, who knew the lease agreement with the city provided for four rent-free days of usage – opening, the timing was right.

In 2001, Fan Fair moved downtown where multiple stages were erected, Fan Fair X opened in the then-convention center and, in 2004, when the festival rebranded to CMA Music Festival (now CMA Fest) Emmy-winning television producer Robert Deaton created a television special to give people a sense of what they were missing.

“I made a seven-minute sizzle reel,” remembers Deaton, outlining the strategy for selling this unthinkable concept. “(Attorney) Joel Katz, (then-CMA CEO) Ed Benson and I went to see Les Moonves to pitch. I said, ‘Rather than tell you, let us show you.’ He got it immediately, no discussion.

“The first year we were on CBS, then moved to ABC. We’ve been there ever since.”

Deaton’s parents, who ran a local country TV show in Wilmington, NC, attended the first Fan Fair. They brought their young son an Eddy Arnold autograph on one of their checks, so Deaton understands firsthand the rush of those interactions. He also understands the reality of asking artists who can earn hundreds of thousands of dollars a night to give up a show day.

“You do an awards show, it is what it is,” Brooks says. “But this show? You’re coming off the road, playing to 80,000 actual fans who are on their feet, singing and clapping. Those deep, rabid fans, you’re giving them headliner after headliner. When you tape that, you show people [who don’t know our music] why country music is so massive.”

Sarah Trahern, CMA CEO and an almost two decade Scripps-Howard senior programming exec, agrees. “Millions of people who’ve never been to the Festival watch the show. Robert really captures what a major event this is: the fun, the music, the artists, the fans. It’s all there. Some see it, then start making their plans to come; others see it and check out the artists. So, it’s another win for everyone involved.”

With $29 million raised since 2006 – earmarked for music education in schools across Davidson County, Tennessee and now anywhere in the nation – CMA Fest helps invest in music’s future. When Conway and Brooks realized music education wasn’t available to every public school student in Music City, it was another reason to press for an event Nashvillians didn’t participate in.

Initial resistance saw other cities raise their hands. Atlanta and Houston came to the table with cash offers to host CMA Fest. Conway, who’d done stadium shows with Willie Nelson and Garth Brooks, as well as several Farm Aids, recognized the odds, “We knew if we didn’t sell 30,000 tickets that first year, we were in trouble. Acts were giving up a prime work night; there were naysayers.

Photo by Nathan Zucker / CMA

“But we have some of the best production people in the world here. We hired Brian O’Connell from Live Nation and Steve Moore, who was at AEG at the time, to answer questions as they came up. We even had promoters flying in to see it, because it was that big.”

Beyond the police, emergency and waste management people, CMA needed the business community. The break came when HCA’s chairman Jack Bovender bought 800 tickets to raffle off among the company’s 8,000 employees; other corporations followed suit.

In the end, they lost $100,000, but more than doubled the number of fans attending. For an emerging artist like Miranda Lambert, who’d come to Fan Fair with her family, Music Fest was an opportunity to connect directly to the people who loved her music.

Beyond a booth at Fan Fair X and fan club parties at the Nashville Palace, she used the event as a launch for her 2014 album Platinum. While an emergency private jet landing and a picture of Lambert and team in silver hazmat suits was all over the media, a Pink Pistol Pop-Up store appeared downtown, Wanda the Wanderer (her tour Airstream) parked across from the Country Music Hall of Fame, posters magically appeared and women in shorts, black t-shirts and short platinum blond wigs were seen all over downtown promoting the record.

“Why not advertise to 80,000 people who were coming to town?” Shopkeeper Management founder Marion Kraft says laughing. “They all went home and told their friends about Miranda and her record.

“And Robert (Deaton) booked her (for the stadium) earlier than most people. She didn’t have a No. 1 in 2008, but he didn’t care – because he thought she was great live. It was a very different performance, 70,000 instead of 5,000 people. Hearing that really lit a fire under her, because as much as we wanted more radio, she realized: she could build her career this way.”

That notion applies whether you’re Lambert, reigning CMA Female Vocalist Lainey Wilson or 2023 Country Music Hall of Fame inductee Tanya Tucker. Tucker’s manager Scott Adkins tactically scheduled Sweet Western Sound so CMA Fest could be a significant piece of their marketing strategy.

“CMA Fest is now this monolithic event,” he affirms. “It’s imperative for any artist who wants to connect with their fans. It’s been 20 years or more since Tanya’s done a signing. This year she’s doing that and a podcast interview from the Close-Up at Fan Fair X; plus she’s playing Ryman shows the week before release and a stadium appearance at Fest!

“She talked about how hot it was back in those barns, the dedication of the fans who’d been there in a lot of cases all day. For her, this is about giving back what they give her.”

Wilson, too, knows that dedication. Her family would save all year to bring her to Nashville. “It was country music Christmas! Everybody played when I went. And I can tell you every place in the stadium we sat in.”

Before the gears caught for the likable Louisianan and she was making ends meet, she lived in a camper in the parking lot of a small recording studio/label. “Every year, they’d let me come and sign autographs in their booth; people’d come up because they felt sorry for me. But I would be in the greenroom with all these other artists, just like I belonged there.”

This week, she will play on the Nissan Stadium stage as part of Robert Deaton’s carefully curated special. It’s not lost on her, even if she’s one of country’s fastest rising supernovas.

Punk/pop sensation Elle King shares that awe over the entire process. Having won CMA Awards for collaborations with Dierks Bentley and Lambert, this marks the outlier’s third stadium appearance. Last year, she even co-hosted the special with Bentley.

“The first time, I was a feature – and I was very, very high on adrenaline,” King confesses. “I had to go find a corner and cry after I played. Last year there were three songs that were mine, and I got to bring my friend Ashley McBryde with me, which was great.

“It’s surprising. People go more insane for ‘America’s Sweetheart’ than ‘Drunk & I Don’t Wanna Go Home,’ which I wrote the same day. But that’s the beauty: there’s this togetherness of everyone who comes.

“Still, I can’t believe they let me keep doing this, because I’m just a girl who grew up barefoot in Ohio. Being part of Music Fest excites me, and people can tell. Between the massive production on that stage, the fact the stars are playing hit after hit after hit and the fans, what could be better?”

Wilson concurs. “It’s that blue collar, lotta pride in what they do audience, who bust their butts every day. My Momma and Daddy are those people, too. They raised me to pull myself up by my bootstraps and give it all.

“[CMA] Fest feels like ‘Open your arms up and come on in! Welcome to our home turf, where all these songs are written.’ I get to see a lot of friends who’re out on the road, but even more, it feels like country music finally loves me back as much as I love it.”

That’s exactly the point. Whether you’re on a tiny free stage or rocking the stadium, the people love the music. All the artists have to do is play – and know how loved they are.