Features

Giants Of Jazz Captured On Film

“First I thought, This is the maid,” says photographer Herman Leonard. “She said, ‘Excuse me, but I’ve got to feed the dog.’ She had a steak in the frying pan, and she was cooking the steak for the dog.”

The woman was Billie Holiday, one of the greatest voices of modern times.

Click.

The scene was sealed forever on film by Leonard, now 86, who captured the odd, intimate moments in the lives of jazz greats. In the last half of the 20th century, he documented the most fertile period in jazz history; the Smithsonian has more than 130 Leonard photographs in its permanent collection.

His subjects range from Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington to Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie. Prints of his photos sell for as much as $15,000 apiece.

Leonard also caught fleeting moments in the lives of those outside the music world, from U.S. soldiers crossing a makeshift bridge in World War II Burma to Marlon Brando playing bongos in Paris. He snapped pictures of Albert Einstein, Harry Truman, Clark Gable, Martha Graham. For a while, Leonard even worked for Playboy magazine.

But it’s his jazz images – masterworks of realism – that won him a $33,000 Grammy grant he’s now using to archive and digitalize the photos. Leonard is the first photographer to be chosen for this grant whose recipients are usually linked to the recording industry.

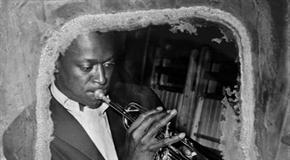

Leonard followed Davis over four decades, from his beginnings as a trumpeter in the late 1940s to 1991 at the jazz festival in Montreux, Switzerland – his last concert.

The trumpeter was known for “being difficult,” Leonard says. “But we hit it off.” At a rehearsal, Davis dismissed all but one of a horde of photographers – Leonard.

“I could see in his face … he knew he was dying,” Leonard recalls.

Those last pictures of Davis “show him in a tremendous amount of anguish.” Still, “he was just glorious. The skin quality was like black satin. The bones were well defined, and those burning eyes of his were so intense that for a photographer, it made it very easy. He was just beautiful.”

The jazz genius was dead six weeks later.

Then, there’s a sweaty, weary Armstrong, sitting in front of open bottles of wine and champagne on a makeshift table during a break shooting the film “Paris Blues.” He’s wiping his lips with a white handkerchief, a lit cigarette dangling from his other hand.

The behind-the-scenes portraits are part of a lifetime of work for which Leonard was honored recently in New York with a Lucie Award for achievement in portraiture. Past recipients include Annie Leibovitz, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Cornell Capa.

“I never worked in my life. What I do is what I love to do,” Leonard said in an interview from the Los Angeles home he shares with his daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter. “I made my passion, my profession.”

He moved to California after Hurricane Katrina destroyed his New Orleans house, just a few blocks from a levee that burst open and destroyed 8,000 photo prints. But 70,000 negatives were saved after being rushed into the vault of a nearby museum.

Leonard discovered his photographic “signature” style by accident, while trying to shoot pictures in murky nightclubs along Manhattan’s 52nd Street in the 1950s.

“My lighting came about because when I was shooting nightclub stuff, the existing light was insufficient,” he says. He found a solution using two strobe lights – one set up in the ceiling next to the spotlight aimed at the performer’s microphone, the second behind the artist somewhere in the audience.

“Then I would position myself so I couldn’t see that back light; it would be blocked by the musician,” says Leonard. “I was able to capture the atmosphere without destroying it.”

The result is seen in portraits that give the subject a kind of glowing aura, while still capturing the smoky intimacy of old-time jazz joints.

Leonard has been called the Charlie Parker of photography. But when asked which musician he’d like to be compared to, Leonard names Gillespie.

“Dizzy could play sentimental stuff with great soul and heart — then go completely wild,” he muses.

Leonard is fascinated by just about everything he sees, from celebrities to dead leaves littering a sidewalk to a man kissing a woman on a Paris street. “He bent over the car with his back to me, and his legs were spread wide apart and her legs were together between his legs – and that’s all you could see,” he recalls. “It’s the kind of imagery that attracts me, with a certain pattern, design factor or composition.”

The images were everywhere he went – living in Europe for 35 years, on the Spanish island of Ibiza for eight years and San Francisco. But it was New Orleans that finally stole his heart.

“There was a warmth and an acceptance there, a certain tolerance,” he says. “You could stand in the middle of the street on your head, and it was part of the decor.”

These days, Leonard hangs out with his much younger staff, sometimes poring over pictures deep into the night. For pleasure, he goes to jazz clubs with friends in the film business, staying away from “old fuddy-duddies,” he says with a chuckle.

In September, the Montreal International Jazz Festival will launch its new exhibition hall with a portfolio of Leonard’s photos.

He is also working on a new book of images to be published later this year. It follows his 2006 work, Jazz, Giants and Journeys, with a foreword by Quincy Jones.

“I used to tell cats that Herman Leonard did with his camera what we did with our instruments,” Jones wrote. “Herman’s camera tells the truth, and makes it swing.”