Features

Executive Profile: Bravado President Matt Young Talks Grateful Dead Tees To Elton John Takeovers

Matt Young, president of Bravado – Universal Music Group’s merchandising company created in part from its acquisition of Epic Rights – still has his very first concert T-shirt, from a Megadeth and Flotsam & Jetsam show in 1984. He had it framed, and it hangs as art in his office today.

Young now carries the weight of a legacy on his shoulders. Epic Rights, of course, was founded in 2014 by the legendary Dell Furano who nearly singlehandedly created the concert merchandise industry. Furano’s professional lineage dated back to his partnership with legendary San Francisco promoter Bill Graham, with whom he co-founded Winterland Productions, the leading merchandising and licensing company in the earliest days of the modern concert industry.

Young was appointed president of Bravado in November 2021, helming a company with its historical roots in Grateful Dead T-shirts but, now, those T-shirts are digital and can be worn by an avatar in a Fortnite video game.

Bravado represents artists in more than 40 countries and provides services including sales, licensing, branding, marketing and e-commerce. Their extensive global distribution network gives artists and brands the opportunity to create deeper connections with fans through apparel, consumer packaged goods and unique experiences.

During the first three quarters of 2022, UMG merchandise brought in $468 million, an increase over the same period of 2021 of $238 million or 96.8% in the first full three quarters under Young.

Pollstar: Merchandising has come a long way since the 1980s and the classic black band T-shirt. What was it like when you were at Blue Grape and Roadrunner, working rock merch?

Matt Young: When I was first starting in the merch business, you only sold two sizes, large and extra large, to Sam Goody, Hot Topic, Transworld Music, whatever record stores were selling it back then. Slipknot came out – and those were some big guys from the Midwest – and said, “Our fans are even bigger than us. We need size XXL, we need XXXL.” It kind of blew our mind. So we’re going to sell them with some damn good prices. You really have to give Slipknot credit for helping expand the sizes. Right after that, the emo bands came out and everybody was wearing tiny, tiny shirts – really tight T-shirts – so we had to go small on all the new sizes.

Merchandise has become big business with major labels acquiring smaller merchandizers and revenue is way up from the beginning of the pandemic. How did the ship get righted?

I think we’re still coming out of it. There’s still some touring that hadn’t happened during the pandemic. And you’ll see I’m touring two or three artists on a bill where they all could be headliners, but they’re on one bill now because they’re making sure they can get back out on the road and have a solid package.

During the pandemic, our DTC (direct to consumer) business, our online business, went through the roof. Fans were home and wanted to support their artists and maybe had a couple extra bucks in their pockets. And so there was an offset in the business where the size of the piece of the puzzle got bigger on the DTC side while the touring side went down to nothing, other than some live virtual stuff.

Most venues are cashless now, so fans can pay for both beer and a T-shirt and maybe a sweatshirt too, and not worry about running out of cash. We’ve noticed massive change there. Cashless really helps everyone. That, combined with the passion and fervor of getting back out and experiencing a lot of music, has really made it. It’s come back stronger on my side of the business.

One of the big the big things we’ve seen in collectibles over the last year or two is the non-fungible token.

It’s much like merchandise. It’s a collectible. It is something that should be one of a kind or rare or experiential. The NFT market in the last few months has kind of not been great, but people still want to collect it. To be honest, it’s still a little bit of the Wild West, like crypto. It’s up and down in its valuation.

Ultimately, our goal in any of the stuff we’re going to talk about is the fan experience – doing what’s right for the fan so that it feels like it’s organic, it’s on brand for the artist and it’s the right consumer experience. And I don’t like using the word “consumer.” I would rather say the right fan experience.

So we’re in [the digital and NFT space]. We know kids live in their video games. And digital merchandise is really the future for us. It is another layer to that digital NFT crypto world, it’s Web3 and the metaverse. And it’s all here already. The kids are already playing all these games and living in those worlds. So we’re looking for ways at all times to be, as we were back in the day with music, where the people are and put the merch there.

We like to say that you can’t replace live. Is that true in merchandising, too?

I will agree with you. But we might be in a generation that feels that way and the younger ones might not at some point.

I was thinking of NFTs as like a digital ticket stub.

You can do digital ticket stubs, for sure. I think what works is scarcity. Being on brand, not feeling like it’s forced. Like Ozzy did with the crypto bats. And that was so on brand and it probably did really well. It wasn’t us, but that was something that felt on brand at the time. I don’t know what they’re worth anymore, but at the time it made sense. As long as it’s part of the lifestyle of the artist and the music.

Then you have a band like KISS, that puts its logo on just about anything that people would buy – and yet, it’s on brand.

There’s some bands that don’t even want their names on their T-shirts. I would try to talk them out of that by showing them how much the numbers would be different if they had their name on it.

But my favorite KISS merch item was air guitar strings. It was a package, just an empty package.

When you came to Bravado, you said you would focus on ensuring artists are reaching fans and new audiences. How do you do that and how successful has that been in the last year?

I think our challenge is that, to some degree, who buys from our artists online also probably has an Amazon Prime account.

What is it about us, or the artist’s store, that makes them want to buy from them as opposed to somewhere else? Is it a cooler, greater, nicer, higher-end, more expensive, more limited product? Any one of those? Maybe.

And there’s some synergy between UMG artists and Bravado to ensure those clients are in those video games to begin with?

One of the competitive advantages of Bravado and Universal is an alignment and the way we work together. Our marketing meetings aren’t about just music or merchandise.

They’re about everything related to the artist brands. And having an artist with both of us creates a synergy in a worldwide capability that doesn’t exist at most other places. You can push a button and have the shirts released around the world. In all the markets we have, we can have web stores in a day and have that sync up with the music and have the label’s marketing teams pushing it around the world. That’s a powerful tool for an artist in this day and age that we can now tap in to.

Do you work much with artists’ agents or management? Particularly at the bigger agencies, full service firms that handle intellectual property, literary, voiceovers and video games that could potentially create a merchandising client?

Certainly. The bigger agencies do have those divisions of the company or people we do work with; not as directly, obviously, as people next door to me at the Universal labels we work with. But they are all part of the team and we get to work together.

Our job is to make the manager’s life a little bit easier by giving them a one-stop shop and to make their artists a little bit more money and everyone a little bit smarter about how to talk to your fans.

Can you give us an example of new innovation, new opportunities for artists? Not just the NFT or the games, but, something general that’s maybe in the works that you can talk about?

We’re always thinking about connecting artists and fans, and that doesn’t have to be

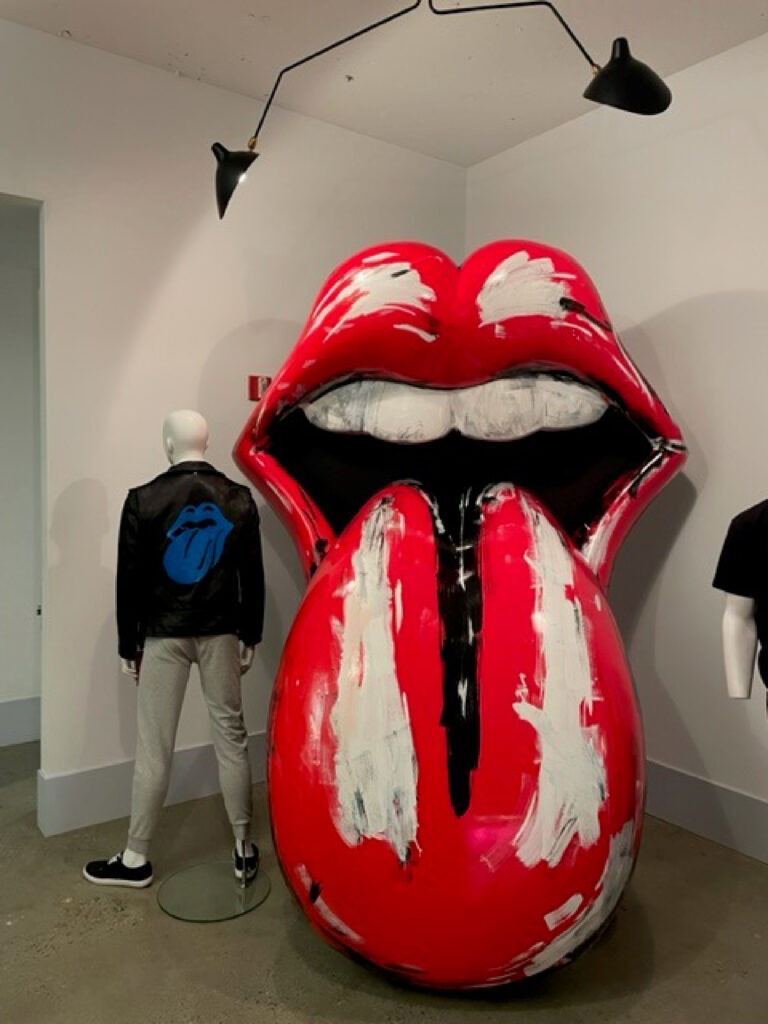

just music fans. We’re announcing a collaboration we did with the football club AC Milan out of Italy and, with The Rolling Stones, we have on Carnaby Street in London a Rolling Stones retail store. We created a brick and mortar retail store just for Rolling Stones merchandise.

It’s all slightly higher-end products, which differentiates it from anything down the road, but think about that – putting a brick and mortar retail store in place in today’s day and age. It’s funny that that’s innovative, maybe, but it works and it gives the fans a place to come and see what’s going on and touches fans in that area of London. Products are all over the place. We’re doing throw rugs and snow goggles. We’re doing a Run-DMC / Burton snowboard in honor of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary. You name it. Merch can be anything at this point.

Along with permanent stores, like The Rolling Stones’ RS No. 9 Carnaby, there have been many surprise pop-ups and other one-of-a kind events that connect fans and artists.

For us, it’s about creating a fan experience. Going to a pop-up shop, you can have limited edition products, maybe the artist is there signing. You can’t get that online. This is what fans want. They want to engage in this passion that’s created between them and the musician. And getting the artists to show up is great. We love doing that. It doesn’t always happen.

We did one in London for The 1975. The band was there, it was open all day. We had gangbuster numbers, but more importantly, the fans got to hang out with some of band and got some photos. But they all met each other and they got to share in an experience, an emotional experience, in the real world.

We did Justin Bieber, and BLACKPINK and Spotify. When that record came out last fall, we did a bit of pop-up with them. We do them for a lot of artists when they tour as a way to have fans engage in the physical product in a way that they can’t otherwise.

Let’s talk about Elton John and his “Farewell Yellow Brick Road” tour finale at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. You did a citywide “takeover” that was a huge success.

We did a very high-end collection at The Webster in L.A. We had something at the Grove in L.A. We did a vegan burger. We had about a dozen activations around Los Angeles, around the Dodger Stadium shows, starting with actual Dodger Stadium activations the week before at Monty’s Good Burger, Urban Outfitters, Lauren Moshi, Abercrombie and Fitch, and a few others that we did. Elton John and David Furnish, his manager/husband, went to a bunch of them.

Another intriguing area is that of merchandising for artists who have, shall we say, left the building. Every year, there is a list of the highest-earning celebrities and invariably Elvis Presley tops the list. What are strategies for merchandising for those artists and their estates?

There’s probably no formula that works for every artist or even within genre. There might be different ways of talking to fans. It’s, again, trying to find those fans where they are and engage them in a way that makes sense to them and feels organic and on brand.

There has been the cycle of the classic rock T-shirts and classic hip-hop designs for artists that are no longer with us. It’s a lifestyle and it’s about what their lives and music meant to people above and beyond whatever that graphic might be on the front of the shirt. And there are a ton of people wearing Grateful Dead shirts out there that maybe have never listened to a whole live show or seen them play live, even if it was with John Mayer.

We had a very successful Tupac lifestyle museum exhibit in Los Angeles, where the merchandise was a big piece of it, and it was about wanting to be a part of that lifestyle. And then we did one on Carnaby Street next to The Rolling Stones. We did a pop-up in Queens, New York, for their anniversary a year or two ago. And that was up for three months. We did one in Japan, in Tokyo for the holidays. It all comes back to emotion and the passion that the music has created with someone and the lifestyle that goes along with that.

Recently, in the U.S. Senate committee hearings about ticketing, one artist mentioned a 20% merchandising fee he said Live Nation took that he found to be pretty egregious. Some venues are announcing they are eliminating any take at all

from merch. What’s going on here?

The venues charge what’s called a haul fee to the artists, usually for staffing up the booths to sell merch for the artist. So the artist pays. It could be 20%; it could be more, or it could be less.

In an effort to sell as much merchandise as they can in a building, and generally speaking in larger buildings, that means that the building will staff the vending booths with people to help them sell merch.

Everyone brings a merch person, but they can’t sell merch by themselves in an arena if they have 15 stands open. That’s typically where they try to justify the whole fee as helping you sell stuff. They should take a percentage of it. It’s sometimes higher and sometimes lower, but it’s a fee that gets negotiated.

For lots of artists, when they’re beginning their careers, it’s how they make a living. Since the Napster days, and with streaming, the music’s getting heard and the economics are slightly different. The merch money on the road helps pay to get you to the next gig and pay and feed the guys, and all that stuff you have to do when you’re on the road. So merch is instrumental in those early days. Obviously, 20% of the earnings that artists make is a significant number. It is a big part of the business. Some artists make more money selling merch than they do selling music.

And some of that income is invariably lost to bootleggers. How much of a problem is that and how do you combat it?

It could be a compliment because at least you’re big enough to get bootlegged! Some people think of it that way, but I’ve done quite a bit of studying that side of the business, and we have some idea of what the percentage is that we might lose if we don’t combat them. But we do combat them at the bigger venues. We hire security to get them off the premises. We do our best to keep them off the property to make it more difficult, and we find out who’s printing them to shut down the printers.

It is damaged goods or off-brand or defective products that they’re using. You’ll notice there’s no label, or the label is cut, which means the blank shirt is damaged. So they get it for pennies, and they print it for pennies. That’s usually poor quality. And typically speaking, anyone who’s a fan of the band who really likes the music knows not to buy that. But there are people that are just there passively and had a good time and want a T-shirt to remember they were there.

It is a dark side of the industry that I wish didn’t exist. But I think as more and more people get passionate about artists, I’ve seen artists fans tell the bootleggers, “That’s a fake shirt, I don’t want it.” And I’ve also seen Mom, with three kids, go buy a bunch.

Does it drive you crazy to go to a big show and see them in the parking lots?

I’ve almost been arrested and I’ve almost been beat up. I chased people around the

parking lot and I’ve created police incidents chasing these people myself to the point where Mrs. Young threatened divorce after one evening of doing it.

I would guess it’s like scalping, where only a small percentage actually takes place at the venue and the rest of it’s online. Would that be correct?

Online piracy is an issue. Bootlegging online is an issue. You can see it now. The change in technology with the printers that can print on demand or the direct to garment printing machines that are in existence now can print one shirt at a time and change the graphic each time.

We’ll see it on Instagram or Facebook. You’ll see these ads – if you like the Grateful Dead, you’ll probably see fake ads for the Grateful Dead. And it looks like it’s custom-made shirts, and that’s all online piracy. It’s like live piracy; its Whack-A-Mole.

We do employ a company called Counter Find who helps us proactively scrub the web for stuff like that. We also have a massive staff of anti-piracy lawyers here that is founded, run by one of the best artist advocate lawyers I’ve ever met here at Universal who chases this stuff online and make sure we do the best we can.

It’s a service. As long as the trademark is registered, we can fight it globally for the artist.

Is online piracy an even bigger threat when we start talking about digital experiences or NFTs?

Like most of those authentic products that are sold on online marketplaces, you have to be legitimate. But there are some that aren’t. We definitely have taken down some illegitimate entities. I think the technology will be at a place, especially if it’s on blockchain, to be able to track that stuff and make sure it’s authentic and the official stuff from the artists because it’s going to all be limited. Or it should be if it’s going to have a value. So there has to be a way to keep up with that.

I’m seeing over your shoulder a banner that says “Artists + Fans” – tell me what that means to you?

That is my motivation. Every day we have to connect fans and their passion with their artists. Every day we have to be great at that. Not just okay. We have to be great.